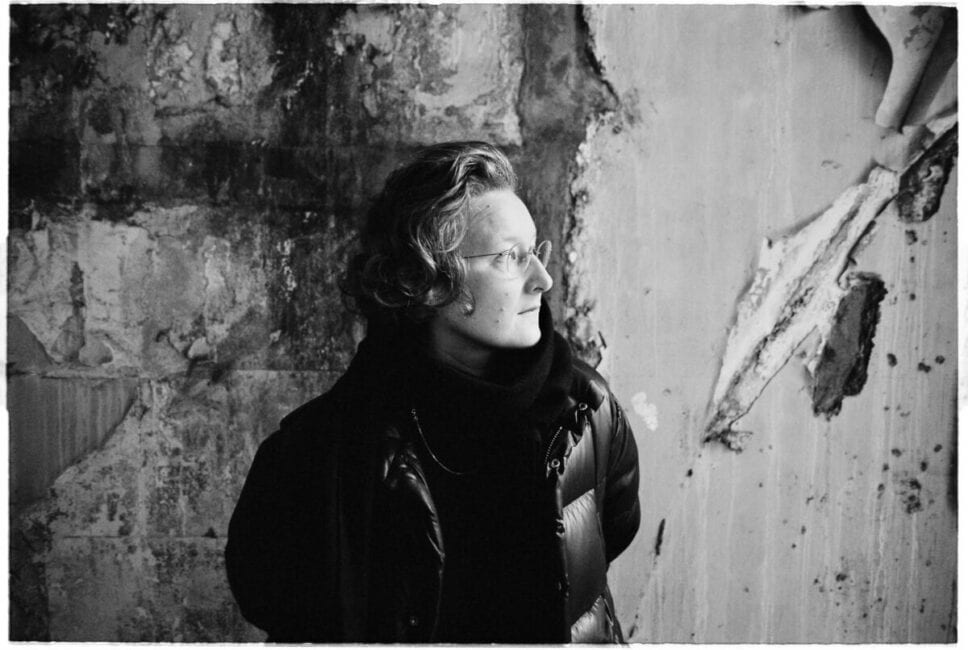

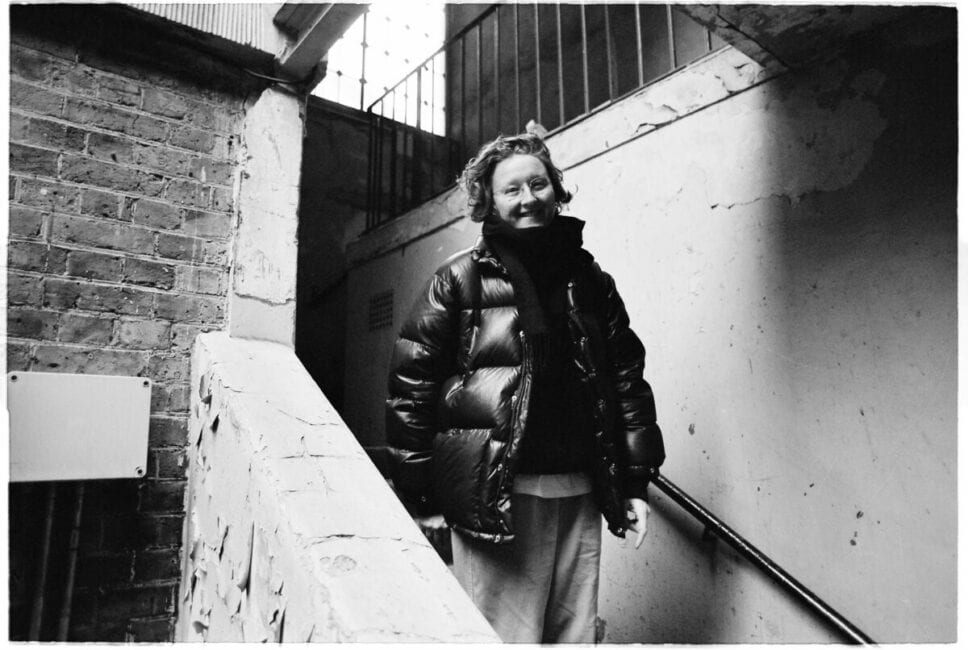

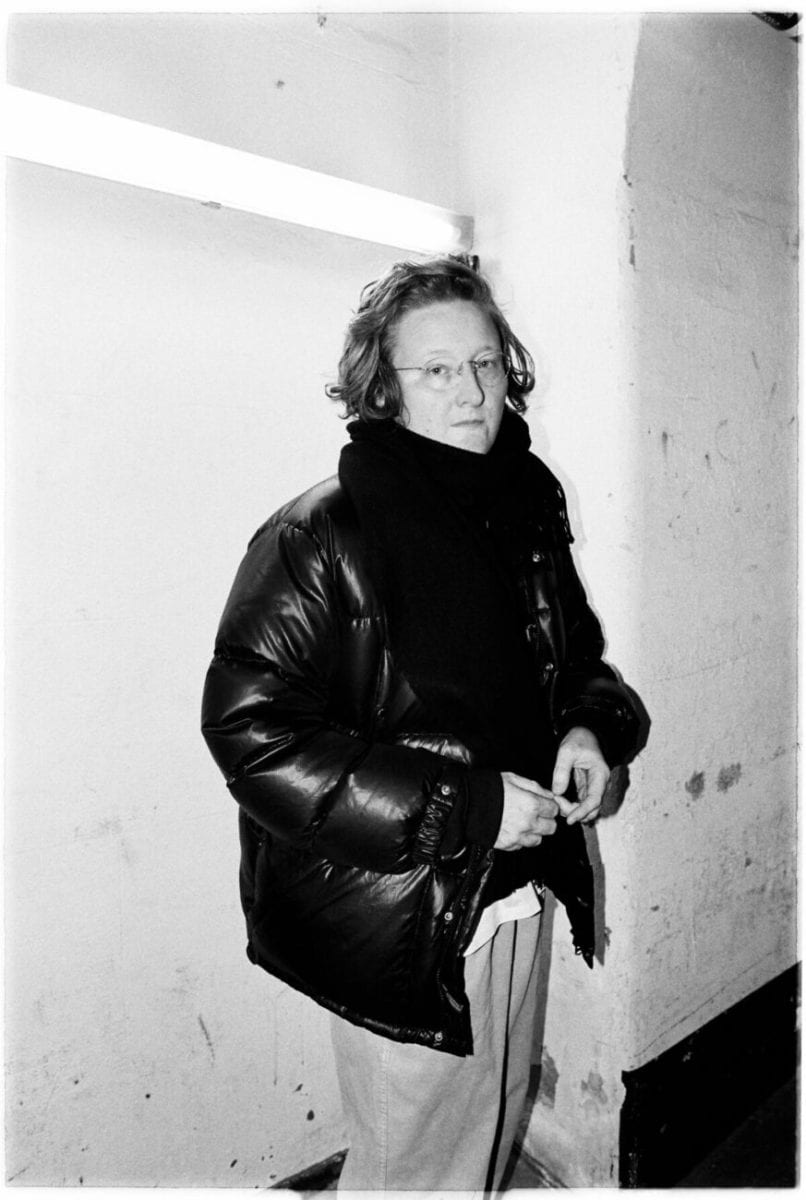

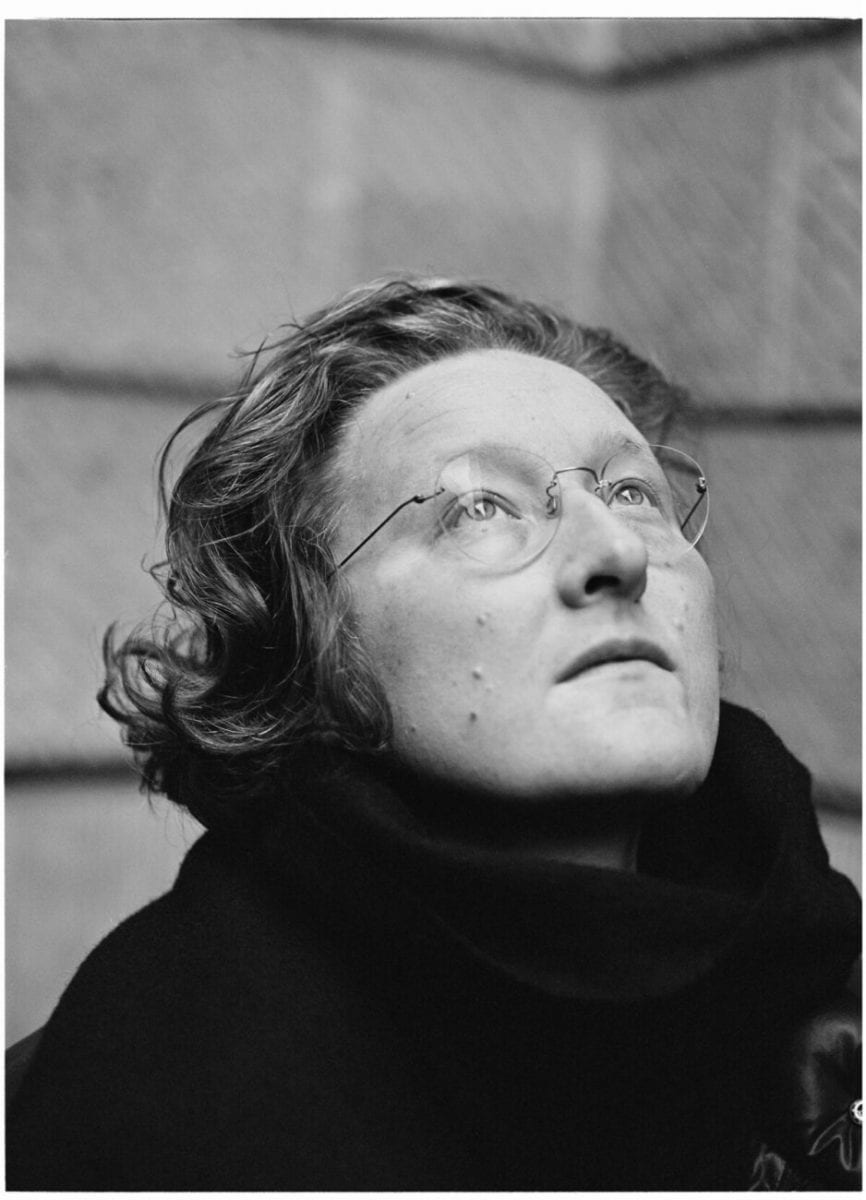

Descending the narrow spiral staircase that led from Somerset House’s ground floor to its underground studio level, I didn’t only enter the hidden depths of a creative and cultural institution. After a two-hour conversation in Beatrice Dillon’s studio and residency space, I left with a deeper understanding of the artistic mentality and creative processes that lie beneath the surface of an adventurously experimental record and the perpetually curious artist that made it.

Much like the music she produces, Beatrice Dillon’s studio is somewhat economical: a handful of prints and posters hang on the walls, a lone bookshelf holds a diverse collection, and two mighty Genelec monitors frame a computer screen that acts as the canvas on which she arranges sounds and manipulates frequencies that make up her intricate and innovative music.

On first listen, Beatrice Dillon’s work can seem highly cerebral or esoteric: music for the mind, not the heart. Though there may be some truth in this – her productions are undoubtedly complex, the result of careful, deliberate work and experimentation – there’s nothing abstruse or overtly academic about them.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Beatrice’s debut solo album, ‘Workaround‘. Her rhythmic constructions possess an immediacy and impact that hits you squarely in the chest, and the myriad of textures, samples, sounds and melodies that surround these patterns are wildly inventive and playfully experimental. The result of an informed curiosity that seems to spring more from intuitive sensibility than theoretical contemplation.

Though rhythms lie at its core, Workaround layers an abundance of synthesised sounds with processed recordings provided by collaborators and talented friends. Alongside saxophone, pedal steel and double bass, Workaround features vocal recordings from Laurel Halo, tabla from UK Bhangra pioneer Kuljit Bhamra, and electric guitar parts contributed (rather unexpectedly) by Untold.

This fusion of the synthetic and the organic, an exploration of the liminal space between the real and the unreal, is a theme that permeates the album, from the use of physical modelling synthesis techniques right through to the album artwork, a contemporary photogram by artist Thomas Ruff, rendered over two weeks in a custom-designed virtual darkroom.

Speaking about her latest LP, Beatrice radiates a fascination with the way that that music works and a reverence for the raw and inexplicable power of sound itself. During our conversation, she comes across as an acutely intelligent but warm-hearted and humble artist, drawing from an innate urge to constantly experiment and explore new methods and ideas. Restlessly imaginative, her approach to composition is mirrored most clearly in Workaround, a kaleidoscopic and fantastical record saturated with boundless creativity.

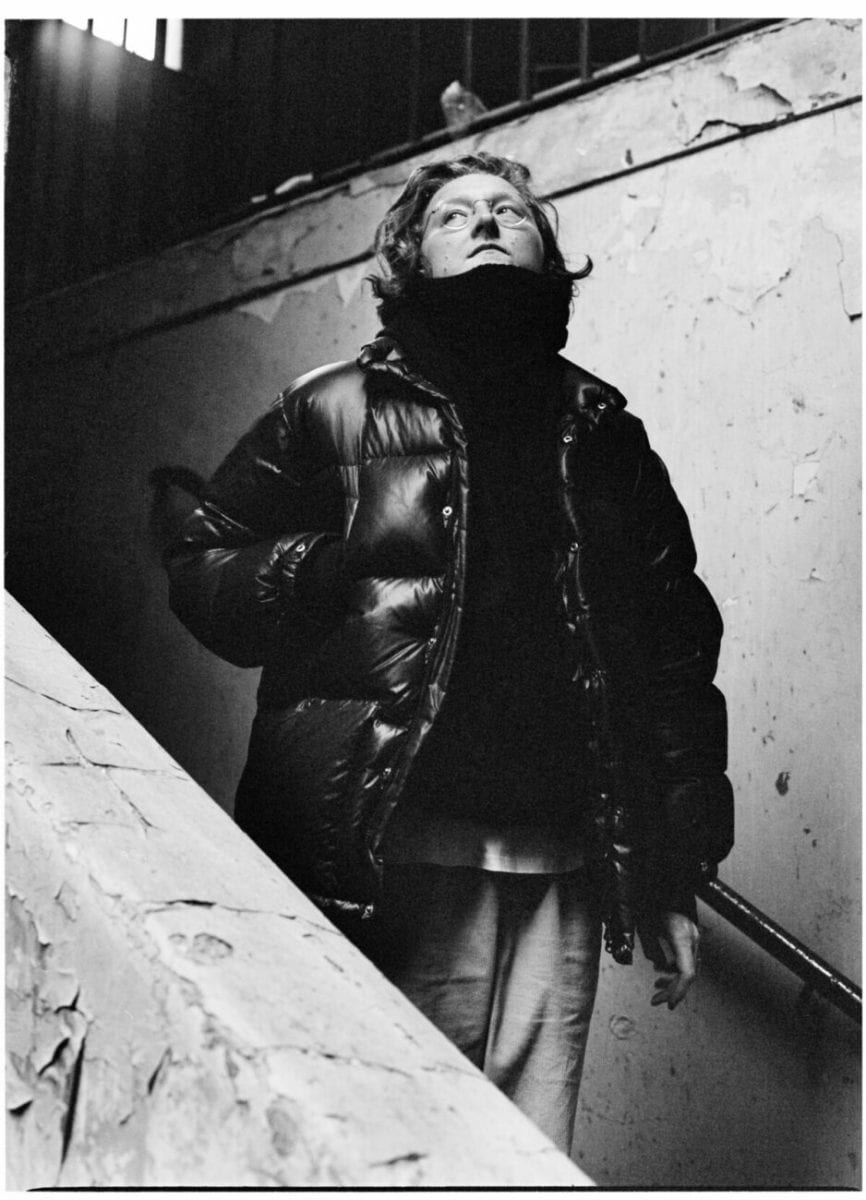

Interview by Matt Mullen - Photography by Alex Kurunis

"Because I was always a music fan, I never thought I’d end up in music, I always thought I’d be on the fringes"

Can you tell me about your background? Where do you think your love of music comes from?

I grew up with Irish music, soul music, and Motown – the stuff your parents play. I was always, always into music. It was apparent from day one. I was getting mad about tapes, collecting them, that was my thing.

What were you listening to?

I was getting everything second-hand from an older brother, so it was all kind of fed through his tastes. Anything from Jimi Hendrix to Bronski Beat. He was really into Talking Heads, so I got into that kind of thing. I don’t know what happened, it just took over and became an obsession.

When did you discover electronic music?

As a teenager I started collecting records – Beastie Boys and Mo’ Wax, all that kind of stuff. Then that spread out into loads of different genres. That was probably when I first got into electronic music, but I never really had a club music phase. I was never into clubbing, particularly, but certain bits of music would filter through. I remember buying a Model 500 CD, and not really knowing who that was… I thought it was so interesting, but without really having a ‘club’ context for it, just being a listener really.

Have you studied music formally?

I studied art – in London, at Chelsea. Because I was always a music fan, I never thought I’d end up in music, I always thought I’d be on the fringes. For a while I was putting on events and shows and doing radio stuff. I worked in record shops for a while – in Rat Records, just before Discogs really took off. Then Sounds of the Universe. Record shops are often empty, you listen to everything, working your way through the shelves – it’s an education.

Music was always in parallel with art. A lot of my work was sound-based, but it wasn’t sound art. I was interested in field recordings, everything you do when you’re a student, recording street sounds for three hours… I actually ended up writing about music, but in the context of art. I was into the history of soul music and the parallel political situation throughout the mid-60s and 70s. History, social history and how music ended up playing a part in that.

Do you think that you take an academic approach to composition after studying art?

I’m not an academic person – the thought of that slightly scares me – I’m an intuitive person. I think an art degree prepares you for nothing, it’s almost the most useless degree… but if it teaches you anything it’s to be analytical and critical, and to focus on what your core idea is, what the essential idea of your piece is. That’s what was left over.

Would you say that your approach to music-making is conceptual or theoretical? Or the opposite – instinctive and intuitive?

A bit of both. Half-conscious. I’m into constraints in projects.. like – I’m just gonna use pink and blue, and that’s it.

They can be oddly freeing sometimes, can’t they, with the amount of possibilities we have?

Exactly. That’s one of the ways of handling working with a computer, is to set yourself limits. And if you bend those rules, that’s fine, it’s just a starting point. It’s often more productive to start with those limits.

Could you give me an example?

So I’m really interested in 150bpm, as a tempo. The whole new record is at 150bpm. The last solo release I did for Boomkat Editions was at 150bpm. And on the first release I did, the track “Carrier/Mask” was 150bpm, too.

To me, that’s a really interesting tempo, because house music is 120 or 125, jungle is 170… and then you’ve got this amazing new stuff coming out of Uganda, which can be anywhere between 180 up to 250. So 150bpm is this weird point in the middle, in between all of those.

It’s certainly not obvious on first listen that it’s all at the same pace – maybe due to the complexity of the rhythms, or the changes in metre?

That tempo has interested me for a few years. Because I generally don’t do things that are in 4/4, you might not be aware that something is moving as fast as it is, but I’m really interested in that, and perceptions of speed in general.

I often think of this example of what’s happening in jungle: you have these insanely fast high-frequency patterns, and this deep bassline, and then the gulf between those two time zones. As a listener, you’ve got so much to latch on to. I love that in music, when it’s not all clocked and synced. I like it when there’s a lot of space to move around.

"Record shops are often empty, you listen to everything, working your way through the shelves - it’s an education"

Are you ever writing in different time signatures?

Yeah, I do – I kind of force myself to do that. In the new record, there’s tracks that are in 5/4 and 6/8… this sounds super academic, but for me, it’s just having fun. And if you’re not doing this 4/4 thing, then you’ve got so much room to experiment. That’s one thing about computers; that linear grid – you start watching the screen and not really listening.

I wanted to ask about your studio set-up and what kind of gear you used to produce Workaround. I can see you have a few modules here, can you tell me about any of those?

To be honest, the whole modular thing doesn’t particularly interest me, that technical obsession with building a synth. I’m not even really sure how they work, I just know that I’ve hit on something that keeps producing interesting results. I’m probably doing it wrong, and I don’t really care.

You might be more likely to stumble upon something different or interesting that way…

Exactly. There’s a little modular instrument there called Clouds, and it’s a very interesting machine. You can essentially load extra software through your PC that sets the unit up as a kind of resonator, so you can run a percussive sound through and the resonator will pitch it and turn it into a melodic element. When I started doing that I thought “I love this, this is so exciting.” I was running a lot of drum sounds through there, along with melodic parts to go along with the percussion, then stacking up layers of those.

If you could only choose one thing to keep here in your studio, what would it be?

The computer. I don’t plug everything in and just jam for five hours, I push bits of audio around on a screen for five hours. I couldn’t make this kind of music without a computer. I’m not particularly into the whole modular thing – it’s a minefield and I don’t understand it, really. I just plug it in and see what happens.

Technically, I’m baffled by it – but it’s also that thing, about that world of machines, where people overemphasise the machines and underemphasise the ideas. I find it unusual to hear music made using modular synthesisers that I think is interesting, or original, or in which the person is telling me something. Often it’s just the machine speaking.

What other elements – hardware or software – can we hear on the new record?

I was using unusual plugins, unusual sequencers, things that force you out of the 4/4 grid of hell. There’s one called Xronomorph – a free bit of software – it’s kind of a visual sequencer, and it shows you the way rhythms work from a geometric perspective. You have equal-sided triangles with an interval between one hit and another representing a rhythmic pattern, and then you can push it slightly off and build a different shape, and you end up with super interesting polyrhythmic stuff that you might never have come up with in any other way. It’s just another way of playing around.

Do you use the Rings or Grids [Mutable Instruments modules] at all?

Rings is specifically a resonator, and it uses physical modelling synthesis – there’s a lot of that on the record actually. Building these sounds that mimic the shape of a three-dimensional, resonating object. That ties in to working with acoustic objects.

It sounds as if many of the sounds on the record blend the organic and the synthetic, to the point where it’s hard to tell which is which.

To me what’s interesting about using that is that you’re on a border between something sounding familiar and not familiar, which is the freedom of the computer, and electronic instruments in general… otherwise you may as well just be in a band.

I can hear a kind of talking drum or djembe sound appearing consistently throughout the record – is that physically modelled?

Actually no, that’s an Indian instrument called a tabla. One of the musicians who played a lot on the record is Kuljit Bhamra, he’s a celebrated composer and musician and it is his main instrument. He was one of the key figures in the UK bhangra scene in the ‘80s and ‘90s, mixing house music with Indian instrumentation. I saw him play once and I thought “I love this… I need to have this in my music.” Then amazingly, he said yes to playing some sessions. So that sound you mention is him playing, but there’s me matching it with other sounds too, so you’re not really sure what’s what.

"I’m not particularly into the whole modular thing - it’s a minefield and I don’t understand it, really. I just plug it in and see what happens."

What about the rest of your drum sounds, are they mostly synthesised, or sampled, or both?

A mixture of the two. I have a drum synthesiser with trigger inputs – you can use it as a MIDI instrument, or you can use it with this module, the Grids sequencer. It’s quite complicated, but the way I understand it is that there’s a brain behind the front of these modules: a chip that’s full of the most common drum beats in electronic music, hundreds of patterns, but just the data, the intervals between the sounds. There’s a map of that information, and you can send in a clock from the computer – say I send it 150bpm – then I have these three green dials, which correspond to a sound that you choose. In this case, kick, snare, hi-hat, for example, and then I can dial in the density of the drum pattern.

Then, these X and Y dials – this is where it gets really interesting – allow you to interpolate multiple patterns on an X and Y axis. You’re on a drum beat, you’re on a loop, and you can kind of swerve into one and out of the other, merging the two. If you just think about how many combinations you can create by finding different values between these axes… There’s also a chaos control, which is a kind of randomiser – when it’s off, it’ll loop the same pattern, but if you dial up the chaos, it’ll constantly generate new versions of the same pattern, never repeating itself. It’s a piece of genius, really, it’s amazing.

You could do a whole record with that!

Well, I kind of did. [laughs]

I know you often work with other producers or musicians, but this record seems like your most collaborative to date – I know you’ve brought in Batu, Laurel Halo, Untold, and other players to contribute – can you tell me anything about their roles?

Firstly, I just really like them… those three are originals. They have something to say. Untold is kinda interesting. He released a record a few years ago called ‘Doff‘, on Hemlock Black, the extra-weird series that he put out, and it’s amazing. There’s this wild electric guitar sound that does this really interesting panning, and when I heard it I thought: I’d love it if we could do something like that. So he’s done that – he’s played guitar on the record. I thought it’d be really cool to get a techno producer to play electric guitar.

It’s hopefully a record full of little things like that, that if you’re interested in, you might pick up on. He played loads of tiny little details that I cut up. Laurel did some vocal parts that I cut up – she read some bizarre poetry on the single [Workaround Two] for me. It doesn’t really matter what she’s saying, it’s just another texture. She slightly pitched up the vocal, and filtered it.

There’s some other real instruments on that track, is it a double bass on there?

Yeah, it’s definitely on the record. That’s a friend who’s an amazing double bass player. Again, it’s that thing of having a real instrument in a real room – which is the antithesis of a computer in a box. It’s that contrast that interests me. For example, one of the key things about this record is that I really didn’t want to use much reverb at all. It’s really deliberately dry and gated.

It certainly sounds very spacious and clean, and I suppose that’s the lack of reverb, and the gating of the drums.

I was DJing a lot, and I got frustrated that I had to wade through so much music that had so much unnecessary reverb on it. I don’t want to diss anyone – it’s a useful tool to glue things together and give an atmosphere – but I also think that it can be relied upon too much. So I thought, what happens if you take it away? Oh my god – it’s really frightening, it’s just empty space… so how do you make it captivating?

So another constraint, in a way?

Maybe, yeah. Not relying on these things that can be an easy way out. I mean, I love reverb – Basic Channel, go for it, and reggae. I think that though it might not sound like it, this record is really influenced by dub. In terms of the economy of sound, and the absence of a narrative within the music, but just… moments of things coming in and out.

A reggae record is a song, someone’s written a verse and a chorus, but a dub is a total deconstruction of that. You have these fragments, hovering, and you get into the vibe of that and there’s no need for a narrative and a story. That’s what I took from dub, not the echo and reverb. I mean, fundamentally, what is dub about? It happens to use reverb and echo, but what it’s about is space and economy and fragments, and your brain fills in the rest.

You’ve mentioned narrative – each of the tracks on Workaround is numbered, is that a form of narrative or structure?

I struggled with the title of the record, actually. Usually things come really quickly. And then I just remembered this word. What I think that word means is: here’s a set of questions, and here’s some outcomes, but they’re not definitive. They’re not conclusions. It’s a little bit like a jigsaw; you throw the pieces all over the table in a certain order, and then you rearrange them in another.

"Ruff thought about how you might make a photogram now, asking: what’s the most contemporary way of approaching the principles behind this process?"

So a ‘workaround’ is a kind of method? A way of putting elements together?

Exactly. It’s probably also tied in with that idea of a ‘version’, a club version where you’d have version one, two, three.. an endless reorientation of the same palette of things. And once you get into that, you’re not thinking about a conclusion or a narrative, just the process of rearrangement.

There are a few tracks – ‘Square Fifths’, ‘Pause’ and ‘Cloud Strum’ – that are not in sync with the rest of the names. Could you tell me about those? One track especially interested me, ‘Pause’, as its only twelve seconds long…

‘Pause’ was made using physical modelling synthesis, it’s that interesting bell-like sound.

I love the idea of forgetting the usual conventions of duration and saying: “here’s one sound, for twelve seconds, and that’s enough.”

Yeah, I think it’s probably that. A breather after all the mad rhythms…

It seems to me that this record, and your music as a whole, is primarily rhythmic – rhythm is a focus, as opposed to melody or harmony, for example. I was wondering where this comes from – are these coming straight out of your imagination, or are you looking at other cultures, kinds of music, or producers for inspiration?

I really am not sure where this comes from. I could list all sorts of people who are influential and inspiring to me. I’m a big fan of the Bristol sound: Livity, Batu’s Timedance… a lot of their music is so inventive and original, it’s such an experience in a club when you hear those tracks. It’s so exciting. And you’re not sitting there thinking “oh, how’d they do that?”, you’re really just feeling it.

Then, for example, I’m really into somebody like Mark Fell, I think he’s an amazing artist. The way he thinks about rhythm and keeping a sense of motion, without repetition. And I’m really interested in a lot of African and Indian music, where timing structures are different… even folk music, Irish music. Rhythmic music that just dances around, like little brain puzzles.

I was in Dublin over the weekend and a friend took me to the pub and they were playing some live music, and I could just see it – probably because I just stare at a computer all day long – most musicians using a computer probably see music now, or they see the waveforms. You get a sense of the movement of something and visualise it in your head.

[Beatrice points to some wrapping paper on the wall, made of a frenetic pattern of lines and dots.]

That’s just some wrapping paper I found in a gift shop, but I thought: wow, I need to make some music that sounds like that looks. That’s literally somebody’s Christmas wrapping paper, but to me, that’s rhythm.

In terms of the way you’re putting together your rhythms, do you ever go off-grid, starting with a blank canvas?

There is a bit of coding on the record – have you come across this program, Tidal? It’s a coding environment you can use for SuperCollider, a live coding type of thing, used in Algorave. A friend of mine taught me how to use that.

I was going to ask if you’d ever worked with Max/MSP, or anything of that nature.

Funnily enough, I just took a short course in maths, to get started. That’s on my list for 2020, to get into Max – I’ve done a bit of it, but really nothing. It seems like you’re finally free, from the grid of hell – it’s a step in the right direction.

To my ears, many of the tracks on Workaround could potentially fit in a DJ set, or work in a club environment, but they certainly don’t sound as if they’ve been made for that purpose. Does that consideration of environment or purpose have any influence on your creative process, or is it completely irrelevant?

What plays a massive part is the possibility of hearing the music on a club PA. Not necessarily the environment, the implications of that environment and the setting of a club night. There’s value in that, and there’s millions of people who are better at that than me, but I’m no good at that and that’s not my skill. But what you can do on a club PA is amazing, and you can’t do that in a regular music venue, it’s not built for it.

So it’s mainly the possibility of hearing the music through a club’s system, and the way that the sound will be carried by that and create an experience, for you and the listener?

Yeah. The way that you can create a huge amount of sub pressure, and these really interesting frequency changes… but it all requires a really big soundsystem. I’m not trying to say I’m an audiophile, not that – it’s just such an amazing experience in a club where the system is really good.

"The interesting thing about music is how fast it reaches your…spirit, for want of a better word. That’s incredible"

Would you say that you’ve arrived at your particular sound through a natural evolution of your creativity, a spontaneous process – or is it something that you’ve pre-conceived or consciously strived for?

I think it’s probably the former. The style changes along the way but the ideas are the same, the foundation that I’ve been interested in all along. Space, and bass, how you make frequencies, and rhythm.

Do you feel that music-making has to have a purpose behind it? For instance, some people might say that it’s self-expression – their reason for making music is to express themselves, their emotion or personality. Sometimes I believe that, but I also like to think that the act in itself is valuable, it doesn’t need an external justification.

That’s a really interesting question. Probably the reason why I stepped away from art is that I got fed up of constantly justifying everything: there’s the piece of work, and there’s the text you have to wade through. Whereas music is just this incredible, mystical force, that just gets you first, and then you can think about it.

Some music is a bit dry, and it’s all about the brain first – I love a lot of that stuff too – but I think that for me, the interesting thing about music is how fast it reaches your… spirit, for want of a better word. That’s incredible.

I read this book a few years ago, by Oliver Sacks, Musicophilia. There’s a story of a person in an old people’s home; a case study of someone with extremely limited mobility. They were played some music from a point in their life where they were really happy, and the person slowly began to move freely to the music, just like that. That to me is just goosebumps, it’s amazing.

I feel that more than any other art form, music is the most inexplicable.

Definitely. It’s all the more endless, all the more uncontainable, and therefore owned by everyone. Everybody has a right to respond to it, an instinctive right… it’s really difficult to talk about this without veering into something very woolly.

I wanted to ask why you chose to release with PAN this time – I know you’ve remixed Helm for them, before.

I knew Bill, a little bit, before that. Just as a music fan, I’d been buying their records for a while. Some labels you just trust, you’re like, “I don’t know what this is, but I’ll buy it, because generally the music is good on this label.” I felt that the music was more inspired by visual art this time around, rather than just other music, and I feel like PAN is a label that doesn’t stick to any one type of music, any one type of sound, or one type of visual. Bill reached out to me a few years ago, and I’ve taken my time. I knew that I wanted a really specific type of cover art, and that they would be receptive to it. I could talk to you about the artwork, if you like.

Go ahead.

I actually brought this book in, because I’d like to talk about it… the photograph on the cover of Workaround is by this German photographer called Thomas Ruff. It’s an amazing image.

I would never have guessed that it’s a photograph. It looks computer-generated, in a way. What is it a photograph of?

I’m glad you’ve asked that, because that’s why I chose it. It’s from a series of photograms – they were really big during the Surrealist era. You take some light-sensitive paper, and then place a three-dimensional object on the paper – glass, for example, is really interesting – and position your light source around the object, then move the object to create an image. Glass is particularly interesting, because light comes through the glass, and you get this crazy optical business going on.

Ruff thought about how you might make a photogram now, asking: what’s the most contemporary way of approaching the principles behind this process? Camera-less photography, and constructed shadows, if you like. This [Beatrice points to a photo on the wall] is very much about a 3D object, on a piece of paper, and a physical light source around that. But Thomas worked with a software developer for a long time to build a virtual darkroom from scratch, a 3D-modelling darkroom.

This image [the Workaround cover art] is all made on the computer, it’s complete fiction. And because it’s made on a computer, there’s infinite positions that the light could come from – even contradictory positions, from above, and down, and below, and to the side, all at the same time. These images apparently took two weeks to render on the computer. You could never get that pile-up of shape and shadows in real life.

Almost like an impossible form.

Exactly, which is what we have at our fingertips now on the computer.

Workaround is out now on PAN. Order a copy from Bandcamp.

Photography by Alex Kurunis

TRACKLIST

1. Workaround One

2. Workaround Two

3. Workaround Three

4. Workaround Four

5. Workaround Five

6. Clouds Strum

7. Workaround Six

8. Workaround Seven

9. Workaround Eight

10. Workaround Nine

11. Square Fifths

12. Workaround Bass

13. Pause

14. Workaround Ten

Discover more about Beatrice Dillon and PAN on Inverted Audio.