Canadian sound artist and composer Kyle Bobby Dunn has been recording transcendental drone music since 2005, quietly issuing seminal releases that have received ardent praise in ambient and experimental circles. 2014’s “The Infinite Sadness of Kyle Bobby Dunn” introduced him to a wider audience and still stands tall as one of the decade’s most emotive and expansive experimental works. Drawing from cinematic and classical music as much as drone and ambient, Dunn operates outside of categories, instead viewing the music he makes as a personal and reflective document of his experience, as “soundtrack suites” to his own life: past, present and future.

Dunn’s latest record, ‘From Here to Eternity‘, is his longest yet – clocking in at just under three hours, it’s an astonishing insight into the imagination of one of contemporary ambient music’s most singularly gifted artists. Marking a first for Dunn, it features collaborations with a range of likeminded producers, contributors who have stepped in to add their own personal touch to his stratospheric symphonies.

Barely a month after its release, Dunn shared FTHE-B, a collection of out-takes, demos and alternate versions of works made during the recording process for his latest full-length release that almost equals the original in length. Deliberately left “unedited and largely incomplete”, it provides an alternate perspective on the pieces that make up From Here to Eternity, and together with the original, it comprises what is undoubtedly Dunn’s most fully realised work to date.

Though each of his releases has widened in scope and developed in technique, Dunn’s recorded output has centred around a fundamental approach to sound that’s become recognisably his own. Through the use of electric guitar, organ, audio treatments, and meticulous post-processing, he conjures empyreal realms, each track a boundless universe that sounds as if it spans lightyears.

Forged from majestic chords and motifs that repeat, mantra-like, folding into one another like the shimmering waves of an aurora, his compositions produce the same wide-eyed sense of awe and quietude that one might feel when observing such celestial phenomena. This sense of the sublime is coloured with an existential melancholy, creating a curious union of inner emotion and outer space, projecting the most intimate and personal aspects of our experience outward and upward across a sonic canvas as wide as the night sky.

We were fortunate enough to have the opportunity to speak with Kyle about his latest (and possibly final) record, taking an exploratory look into From Here to Eternity, his creative process, and the emotional inspiration behind his work as an artist.

Interview by Matt Mullen

"Sometimes you have to see through a lot of ugliness to let the beauty shine a certain way. This album feels like the sadness is forever there, but there is something beyond it as well"

Your latest record, “From Here To Eternity”, is your first since 2014’s “The Infinite Sadness of Kyle Bobby Dunn”. Would you say that this record is a progression, a continuation of your previous work, or a diversion into something new?

It’s all of those things and none, I’d say. I’ve been working on diverse works over the last decade, and some things just never really turned out or sustained themselves. When I forced myself into the lab to work on these loops that eventually became ‘Infinite Sadness’ in 2014, I had decided to take everything in a certain direction emotionally, but still surprised myself with the warm moments on that record.

In listening to it or comparing it today’s new album it feels so much warmer and even child-like. The latest record is really the more brutal realisation of that album, and maybe a more realist vision of the fantasies that were all over the place on ‘Infinite Sadness.’ It is a progression maybe, but who says progress is so great? It’s a lot colder, but I would argue more real, and like Trent Reznor said about his 25 year old epic, ‘The Downward Spiral’: “I made a small scale, personal, potentially ugly record that reflected how I felt.”

I agree that Infinite Sadness felt warmer, more intimate even, than the new record. You describe FHTE as a brutal realisation, as more real and cold. Were those qualities you consciously set out to achieve in the studio?

Some of the sounds are as old as the ‘Infinite Sadness’ LP and were originally composed shortly after the release of that album. The other newer sounds, I suppose they came out sounding broken and confused. ‘Triple Axel on Cremazie’ was recorded on Valentine’s Day 2018, I just remember feeling a sense of sadness that was full of ugliness – whereas some of the moments on the older album were sad but beautiful. I guess there is beauty in the ugly too. Montreal has a lot of that. Sometimes you have to see through a lot of ugliness to let the beauty shine a certain way. This album feels like the sadness is forever there, but there is something beyond it as well.

Bandcamp tells us that the tracks were composed from 2012-2018 – has this album been six years in the making? Could you tell us a little about the story of how the latest LP came to be?

After ‘Infinite Sadness’, there were loops and documents that remained unfinished – not everything could fit on that album. I was still refining things, and then would stop for long periods of time and see how something aged or felt after a while. I found that process is what made the better suites on ‘Sadness’ work so well.

So there were pieces from 2012, that were initially set for the Sadness LP, but didn’t make it for my own neurotic reasons or just didn’t fit in. Then there’s work that took an entire year to process or think through: ‘The Flattening’ took forever and still should have been longer perhaps. Always scavenging the vaults of my ancient computer and seeing what old loops or fragments of works still stick in my head, or can garner some kind of deep emotional response after a long time away.

I knew I wanted some continuity with ‘Infinite Sadness’ because that record felt like it was going to be my final release – I was satisfied with the concept in many ways – but the more I worked on new material, and the more ominous-sounding things came out, the more sense it made. I don’t want it to erase the air of the last album, but in some ways it forces you to see everything as eternal blackness – and maybe it burns out like the stars and all of us do eventually.

"There are moments that it does feel like evil is winning in the world, and the music is a reflection of that. Even the warmer pieces on From Here to Eternity have this evil lurking beneath, above or throughout them"

You mention that some pieces took an entire year to process and think through. Could you elaborate on what that process of refinement looks like?

Sometimes it’s about the EQ and sound process. ‘Macleod (And the Victims of Deception)’ from Infinite Sadness took years and years for me to feel good about sound-wise. ‘The Flattening’ and ‘Alpine ‘88’ were just sitting there and being changed in detail over a long period of time. I sometimes just walk around listening to it and take in how the sounds make me feel, and if it clicks it clicks. Sometimes it’s a discarded loop or recording that changes everything.

In your previous answer you suggested that ‘Infinite Sadness’ was intended to be your final release. What was the reasoning behind that – did you feel like your creative process had reached some kind of conclusion?

I felt the statements made on ‘Infinite Sadness’ were enough in many ways. I also felt deflated and exhausted after working on it for such a long time. In a way it should have been my first and last album. It made everything else I had made seem pale. The new recordings just started following me around like a shadow, more and more, and my returning to the process felt like a struggle – and that evil was trying so hard to sink into the pieces.

There are moments that it does feel like evil is winning in the world, and the music is a reflection of that. Even the warmer pieces on FHTE have this evil lurking beneath, above or throughout them. Some are like the sounds I felt soundtracked my dreams that I can recall from years and years ago, in my childhood days even.

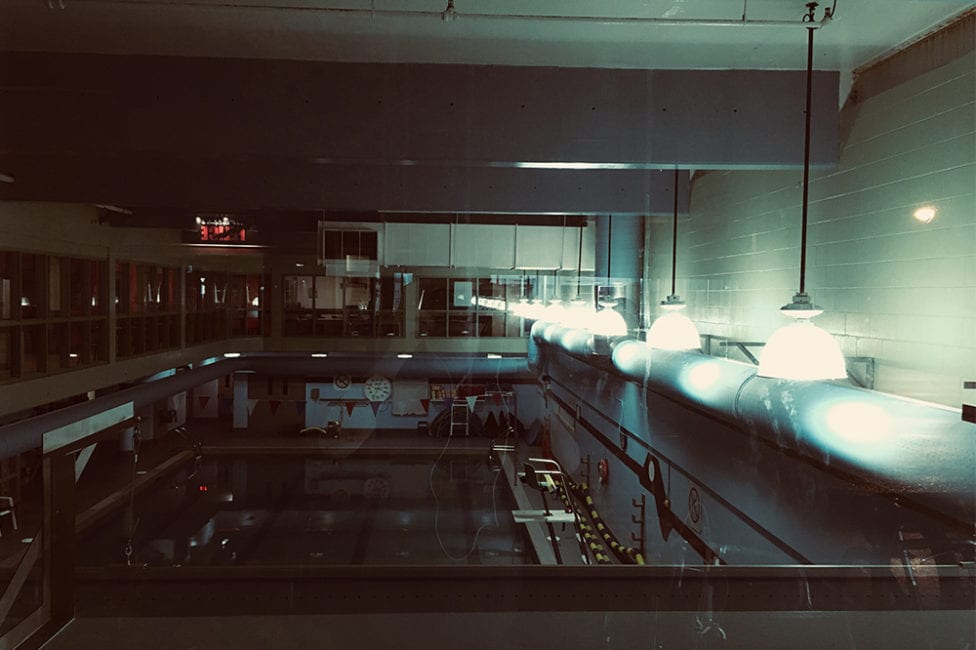

‘Dead Calm (Southcentre Suite)’ is all about these totally bizarre memories that linger on from my childhood in Calgary. Like the basement of my home there. The eerie empty parking lots. The ghostliness of times past and how it seems like none of it even happened at all.

You’ve worked with a long list of collaborators on “From Here to Eternity” – that’s not something we’ve seen on your previous albums. What compelled you to work collaboratively this time around?

I really wanted to work with guests that have touched me personally and musically in my own life and it was not as collaborative as it sounds. Most of these musicians had to meet my sound accurately enough so it wasn’t open to a lot of interpretation, though I have recently released a B-Sides and Variations album with a lot of that material that I still really enjoy.

It was just that some artists I asked to contribute really had their own voice at the table. Certainly the engineers and the creative continuity offered to the album has made me see the album as something even unique to my ears. Working with complete outsiders and kind strangers on sensitive production and audio treatment was so interesting. To feel how they actually saw the tracks and changed them from the ground up was incredible. These folks are, in my opinion, making some of the best music in their own solo endeavours and projects currently available today.

In my view, FHTE feels like a real progression from your previous LPs. There are more perceptible sounds, instruments, and field recordings in the mix, sitting alongside the drones and harmonies. The music feels more complex, layered, and slightly darker in tone. What compelled you to embrace a subtly different kind of sound?

Everything comes from the state of our times and the history of the self. The cover art is an example how everything in the mind is like movie stills. You remember everything, even if you don’t want to. I wanted to make a concept record about the concept of one’s life. The warmth and milk of kindness and people that come in and out of it. The horrors of the self and the ageing process. My own struggles with terminal illness and isolation. Fears of repetition in just about everything in life. It’s also about letting go of a lot of the gripping emotions and feelings I had on the last album. Embracing the violence and trying to put it into sounds rather than my own life.

I love how the recording process was varied and different. The post-production with Maryam and Milad was easily one of the most incredible parts of working on this. They took many of the quietest moments and turned them into velociraptors escaped in the park.

Over the years I have been taking in more and more old films and am strangely haunted by really bad ‘80s horror and slasher flicks – some that I even took in at an incredibly young age when video stores were still open. Those sounds found their way into moments on the record. It always feels like I’m soundtracking my life, and I’ve been inspired by even the oddest soundtracks from those kind of films, so it’s something of an homage. It’s a balance though. Everything. Every moment is filled with darkness and beauty.

"I wanted to make a concept record about the concept of one’s life. The warmth and milk of kindness and people that come in and out of it. The horrors of the self and the ageing process"

You’ve said that you wanted to make FHTH a concept record, about warmth, kindness, illness, isolation and fear. I can hear all of those things in the record. With such abstract, wordless music, how do you communicate such universal themes and experiences?

I love the instrumentation and approach I have to the guitar, because I can channel so much feeling through this basic instrument made of wood and strings. It is seriously such a great tool for most musicians trying to convey emotion in almost every genre of music. I think the guitar is so powerful and versatile that even I forget that it is what made these sounds, not me.

Wordless and classical or instrumental music often does communicate so much more to me than folk songs or pop and rock music. Sounds carry such weight – it’s really the most unique medium in all of the arts. Film and painting and visual art really only represents one thing with what they choose to say, whereas sound can be very abstract and open to so many interpretations. It’s like painting or sculpting in the air.

Could you talk a little bit about your compositional process – both technically and conceptually?

It’s really quite simple for the most part. Just an approach I’ve been able to become comfortable with in playing the guitar. I’ve never got really good or wanted to further my music theory, because I was afraid it would take the approach to my playing away too much. So it’s a bit personal and even embarrassing to me. It’s really just electric guitar with some treatments, and I use really old software.

The last few albums have been recorded using Logic Pro 7, which I have just come to find intuitive and simple to use. My guitar playing style is mostly a mix of swells and feedback and then captured moments with the loop station that allow for some structured lines or buildups. I build some reverb patches and things like that, but I like to keep everything pretty bare bones, using as much natural resonance and decay as possible.

This album had me record at different spaces, including a live set that was recorded and engineered initially by Matt Roglasky in 2014 at the Isabel Bader Music Centre. I went to other people’s spaces and tried different microphone techniques out. The organs were recorded in 2012 at a friends studio in Toronto. My studio at home for ‘Infinite Sadness’, and some of this record, was just a small room overlooking the nice street below my building. It looks gorgeous every season and is a comfortable and intuitive work space for me. Nothing fancy.

There’s a lot in your music that reminds me of other ambient and drone artists, but at the same time I would say that you have a truly singular sound. What do you think sets your music apart from others working within that sphere?

We all have a different process, but maybe I am not such a big gear-head or pedal wizard like others might be. Certainly not too synth crazy, like everyone is these days. I also like to think outside the realm of this whole ‘ambient drone’ label – I am never setting out to create a suite of music around that term. They might turn out sounding that way, but there is a bit more involved that seems personal, reflective and compositional, that maybe makes the works differ in feel.

"I often feel that our expressions and silences say more than words ever could. Music and sounds can feel like salvation sometimes, and I certainly also feel a great spiritual effect or enlightenment in my process of listening to the music of others"

How does a song usually begin and grow for you? Is it a matter of improvisation and spontaneity, or pre-conception and composition?

I feel like it’s a mix of all the above. Like I said, I like to see how a track feels to me after some time away from it. It’s nice to forget about something completely, then I stumble on it down the road after I’ve almost forgotten making the initial sounds and loops in the first place, and then add to it. I think we all want to be surprised by what we create. The same goes for a live setting too. I don’t like spaces that are too small, or spaces everyone plays all the time. I want an experience as much as the audience does. My own sounds too – they should carry me somewhere that is not the here and now. It should be deep in the past or light years away.

Do you see yourself primarily as a composer, a producer, or both? What tradition (if any) do you feel your music is born out of: ambient, drone, classical, cinematic, devotional… in my mind, it draws from each of these to produce something unique.

Absolutely. I grew up on soundtrack music and to me these are like soundtrack suites to my own life or my past, maybe future. I feel that this kind of music is the closest to resembling our complexities as a species.

This remark about our complexities really resonated with me. I feel that it’s almost paradoxical, how abstract music that contains almost no explicit meaning, can in fact contain vast worlds of feeling and emotion. For me, listening to such music is almost a spiritual experience – I feel like it speaks to an inner part of ourselves that we can’t reach through words alone.

I often feel that our expressions and silences say more than words ever could. Music and sounds can feel like salvation sometimes, and I certainly also feel a great spiritual effect or enlightenment in my process of listening to the music of others. I was once religious in my life, and those days haunt me, but I know I will never go back to religion in my lifetime. Sound and its universe taught me too much about being human.

Your album notes describe PITP as “a difficult album of unending loss, confusion, pain, identity, disease and even death”. It’s clear that darker themes take precedence in your work, often contrasted with wry song titles that lend a touch of irony to such themes. Could you tell us about the emotional inspiration behind your compositions?

Each is a suite is an emotional affair. I am always dealing with living in a state of infinite sadness myself. Trying to understand or make sense of feelings through music is what a lot of us do, I think. The initial attraction is how it feels to be working on it and then how it sits and works after it’s all finished.

I do think the themes on this record are just a reality check from the last record in many ways. You can be sad, but it doesn’t change how awful everything is. There are moments of complete loss and obliteration, or flattening of emotions on this album. How sadness turns to anger and frustration. There’s moments on it that even scare me or I feel I went too far with.

"There are moments of complete loss and obliteration, or flattening of emotions on this album. How sadness turns to anger and frustration. There’s moments on it that even scare me or I feel I went too far with"

You say “There’s moments on it that even scare me or I feel I went too far with.” Could you elaborate on this – certainly there’s a more audible darkness on this record, as opposed to the glowing warmth of Infinite Sadness.

It’s about this back and forth in some ways, between darkness and light. We are all made up of good and evil forces. Two identities. Things like this. How the comforting moments are more terrifying than the dark and mean moments. I felt that my process and arrangement gave way to an inner violence that needed to be harnessed with sound, but perhaps that sound is too revealing. Too naked. Infinite Sadness went too far: the amount of emotions it opened inside me while working on it drove me a bit insane. This newer album is a confrontation of that insanity and a mirror-like exercise. How scary our own reflection can be.

For me, your work sounds and feels extremely meaningful, despite its abstract and wordless nature: it elicits a kind of existential melancholy, a sense of vast space and deep feeling, and a curious longing for a past that I have never experienced. What do you hope to communicate with the music that you create?

The fact that we are stuck with our own past, or we missed all this other stuff that was happening while we were alive, or before we were alive, is a dark and heinous one to me. The possibility that you just weren’t chosen to experience a certain way of life. It’s maybe an examination of myself through sound.

I am always amazed that people enjoy it and like what I create. But it’s so personal and strange that maybe the real narrative will only ever make sense to me. Even though there’s no words, I think I say a lot through the way the sounds come out.

Place names often feature in your titles. I know you’re from Canada, in which province did you grow up? Do you feel like that environment had an influence on your musical development?

I was born in Toronto but quickly moved to Calgary, Alberta when my parents divorced in the early ‘90s. I loved growing up there for most of my childhood and I think back to it a lot when I am arranging my works. It’s a place that always haunts my mind. I’ve lived a lot of places since but that environment had profound influence on my sounds and maybe even why I started creating in the first place.

What was it about that environment that pushed you towards this type of composition, these kinds of sounds and moods?

Probably this overarching sense of boring, deadpan anglo-saxon community with no real sense or room for character development or individualism. It was also filled with this sprawling beauty that could also be very ugly.

The landscape both warms my heart and fills it with a sense of emptiness, when I think back to looking out at the rockies in the distance of the city as a child. Our long walks to school in the snow and confused mental states in our Catholic school. I was and still am interested in this cinematic effect that all situations in life produce. It felt like we lived in a strange movie a lot of the time. It still does.

‘From Here To Eternity’ is available now via Past Inside The Present. Order a copy from Bandcamp.

TRACKLIST

1. Preludium Aeterna

2. Infinite Escalators

3. Triple Axel On Cremazie

4. Years Later Theme

5. Happiness & Momentum

6. Zendel Holiday Hangover Toccata

7. Boul. Gouin

8. The Flattening

9. September & Her Sudden Drones

10. Their Memories

11. Alpine ‘88 (Soundtrack Suite)

12. Foothills Medical Clinic

13. La Stationnement De Finders

14. Rachel (Hiver Éternal)

15. Dead Calm (Southcentre Suite)

16. From Over To Wendover

17. Videodrones Des Questions

18. Eternity, The Stars & You

Discover more about Kyle Bobby Dunn on Inverted Audio.