For Muqata’a, music is far more significant than a commodity to be merely be enjoyed. Hailing from Ramallah in Palestine has left an indelible mark on the producer’s ethos on music, rooting his compositions in the bracket of ‘resistance music’, that category which in time often forms a cradle for popular modes and genres quite isolated from their origins.

With numerous albums under his belt Muqata’a’s influence in Palestine is echoed in honorific titles, such as ‘The Godfather’ of Palestinian hip-hop — a reference to his musical origins, but by no means a suitable term to cover all of his output: 2018’s album of grating noise and experimental composition on Discrepant showed a broader spectrum of influences, now solidified by a further album through Milan’s Hundebiss Records released in early February 2021.

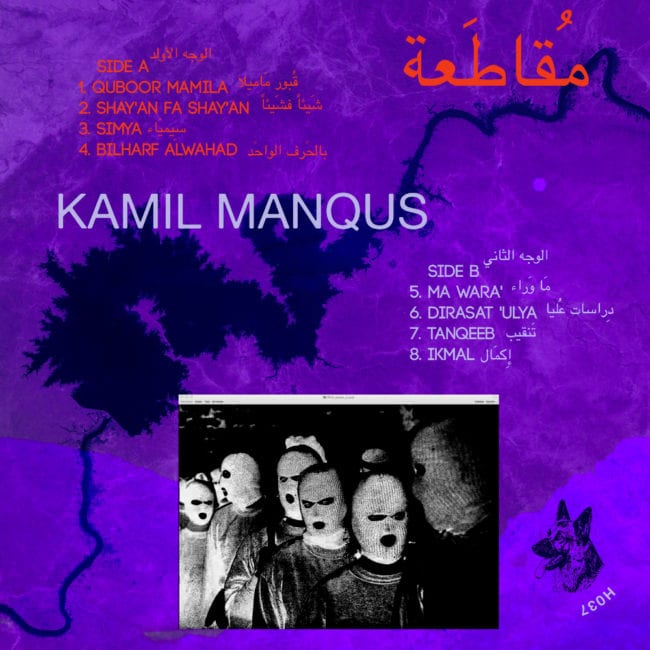

‘Kamil Manqus‘, which translates roughly to ‘perfect imperfect’ in Arabic, is a masterpiece of uneasy, unsettled music, agnostic in regards to genre and a truly expansive addition to the Palestinian’s already versatile productions. A work with the true character of the creator pumping through its veins, ‘Kamil Manqus‘ is one of the most essential documentations of Palestinian music to have emerged in recent years, and will doubtless prove to be so for many years to come.

Speaking to the producer in his new home of Berlin, in this full-length interview we had the pleasure of discussing the seeds of the album, the real-life implications of living under Israeli occupation both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and what it means to create resistance music.

Interview by Freddie Hudson

"It was an interesting concept for me to try and communicate with my ancestors, to document our history before it is erased."

Hi, thanks for speaking with me. I hear you’re now in Berlin, not in Palestine, I was wondering what provoked the move?

The main reason was for performances. I had a few lined up in 2020 and pretty much all of them were based in Europe. So personally, it made sense for me to relocate to Berlin. It’s very expensive to travel back and forth from Palestine to Europe, and is also a difficult process.

Being based in Palestine made it expensive to book me to perform — travelling to Jordan from Palestine alone is costly, something like €300 to go there and back, and then a ticket from Jordan to anywhere in Europe is not that cheap. Then you have the performance fee, plus accommodation and so on. All of this adds up, as if you’re booking a superstar. I was missing a few shows just because of that

Was getting booked in Europe last year a relatively new request, or has there always been demand for your music?

I’ve been performing in Europe since 2007/8 as part of Ramallah Underground, then with Tashweesh, which was a group we started in 2010 consisting of Basel Abbas, Ruanne Abou-Rahme and I, who are also the ones who began Bilna’es.

Usually I have one performance per month, therefore I have to travel to Europe for that show, return, then head to the next. In 2019 I did some small tours and in 2020 I had even more shows being booked, so I decided to be based in Berlin for a year and see what happens. Then the pandemic happened and pretty much all of the shows were cancelled.

Is there any hope that these shows will be put back on?

It doesn’t seem like this particular sector is going to be back anytime soon, performances and gatherings.

I guess there are more opportunities here in Berlin in order to get your name out and doing performances that are live-streamed?

I’ve done four or five streamed performances since the pandemic began, but it’s hard to meet people, because nobody is meeting anyone at the moment.

So when did you leave Ramallah?

I left in February 2020. I had a performance in Athens at Movement festival, I did the performance and moved to Berlin afterwards. I arrived, and then COVID-19 broke out.

I remember watching Boiler Room Palestine live a few years ago, and on the face of things it seems it did a lot of good things for the scene in Ramallah and Palestine, such as boosting the visibility of artists like yourself and Sama’ [Abdulhadi]. I’m keen to understand how it was felt locally?

I think Boiler Room, with it’s documenting what’s in Palestine, and putting it out on their platform helped spread the word in a big way. It was very good exposure for all the artists that took part. Before Boiler Room I used to travel and perform regularly, but after there have been many more shows. In that sense, both the live stream and the film really helped spread the word about Palestinian artists.

Even for the people who didn’t perform at the Boiler Room event, it helped open more doors and, in a way, made the scene more legit. I mean, that’s not 100% correct, I think it’s always been legit, but it gave this feeling that the world is watching, and we’re doing our thing. They made a very big political statement by saying “Boiler Room Palestine”, not “Boiler Room Ramallah”.

A lot of things happened around that same time as well. A friend, Mayss Naber, sent the video of my set to Drew McDowall from Coil, and he shared it online, and also wrote about one of my EP’s being one of his top 5 discoveries of 2018, since then I’ve been getting a lot of bookings as a direct result of that.

"There’s also the matter of the urgency in Palestine to produce music, to produce anything, which brings us all together"

With the stream, you said it ‘legitimised’ the scene, even though it was already legitimate. I think the thing it did was really show the scene as it is, more than just one or two individuals, but really a network of people working between there and Haifa.

That was really important, it had a good part of the story of how things were formed, in a way.

There was the nice section at the beginning of DJ ODDZ jumping the wall to get to a gig. Maybe the most contentious lengths the documentary went to, but it really showed that the music there is proper underground resistance music.

Exactly. By the way, ODDZ started his own festival in Palestine called Exist. That’ll be starting up as a label, their first release will be coming out soon.

I saw snippets of Anthony Linell and Sam Binga performing there last year, it looked really great. I was impressed to see that, particularly as I know these types of parties often get shut down… Jumping ahead, about the album: I find it interesting that it’s coming out on Hundebiss, especially as they reissued Shabjdeed & Al Nather’s album, which was amazing to see. I’m interested in how the opportunity came around?

Around two years ago they got in touch saying that they were interested in releasing an album. Also, in that same year, I performed with ZULI at Unsound, as an MC. I met Simone from Hundebiss Records and we talked a bit more about the idea.

Since we’ve been talking, we’ve dropped the word ‘scene’ quite a few times, but the word scene kind of makes it feel like something too commercial. Obviously there’s a network of musicians and there’s a lot happening within Palestine’s music world, but perhaps scene is underselling what it is?

I agree. For years we’ve been calling it a ‘scene’, and waiting for it to become a ‘scene’, for lack of a better word. But I think at one point we realised that, whatever a scene is, ours doesn’t have to be about that. It’s more about what we’re doing with our music, what we’re doing together with this very diverse community that we have.

Community makes more sense, as scenes are directed at a specific kind of music, or genre. I feel that the scene, in Palestine, is more of a movement or a community. We have the people that produce noise and they’re present at trap events, and the people producing techno are at the experimental electronic events. The people that are from that scene are more of a larger group of artists that are actively supporting each other, and supporting the diversity of the community and movement.

Ramallah is a small city and Palestine is a small country. It makes more sense this way, it’s more organic. There’s also the matter of the urgency in Palestine to produce music, to produce anything, which brings us all together.

It’s not about “I make hip-hop, you make techno”, it’s more about what we are doing for our community, what role it plays in the grander scheme of things. Our culture is being erased, our history is being erased, our archives are being destroyed. So what are we doing?

The reason I sample old Arab music is because I am trying to preserve it before it is erased. When Palestinians were kicked out of their villages and cities, which is still happening to this day, a lot of people, including my grandparents, left their record collections in their home as they fled. For me, trying to sample that specific music is a statement to regain access to those records.

"I wanted to pay respects to those sounds and movements. They were all political movements, not scenes"

I think it’s a really powerful mode of re-contextualisation that comes through in the music you have released. Having listened to the record coming out on Hundebiss, it is clear that you are returning to the same sampling techniques you’ve used before, but for a hip-hop producer there’s a bit of jungle in there.

I’m interested in hearing about why you chose to make that music in particular, but also about the mood – it’s broader in approach to ‘Inkanakuntu‘, which you released via Discrepant, maybe. Did the fact that the album was being released via Hundebiss Records, a ‘proper’ dance music label, have anything to do with it?

Honestly, it was more personal than that, it was something that I wanted to do. It has a lot to do with me being influenced by early jungle and drum & bass. Since I was younger I listened to a lot of these genres, and others coming out of the UK like trip-hop, garage, and early dubstep.

This influenced my work for a long time and I wanted to pay respects to those sounds and movements. They were all political movements, not ‘scenes’, as we’ve discussed. It had a lot to do with where the music came from and why it was made. This is something we should all learn from. It’s very similar to how the hip-hop scene started in the Bronx, NYC. It was to do with protest, resistance music.

These sounds of the oppressed, who want to break their oppression, are very relatable. For me, it felt like the right time to use those sounds in the same sense as I use classical Arab music. I felt they’re both going in the same direction. Together, they can give a different message. It has a lot to do with uniting different movements. I also see the sound of jungle and hip-hop or trip-hop as my sound.

It was a surprise when those tracks kicked in. The thing that really struck me was this tangible resistance within it. I think a lot of these genres are being twisted into these high energy club tracks, and it loses a lot of the reasons as to why this music was being made. The tracks on the new album don’t have that ‘lets make people go wild’ element.

Yeah, I didn’t go with the standard drum & bass tempo, because I am not trying to recreate that. It’s slower than what most people use this genre for — they’re both at 145bpm. It became a go-to tempo, I don’t know why, but it worked for me.

It’s interesting, slowing it down and bringing it back to the original message — you can hear it in the record. Can you talk about broader inspirations behind the record?

[When] I started working on this record, I didn’t have a specific idea in mind. I went with the flow, producing different sounds, sampling from the radio. I knew I wanted to use live radio sounds, because I wanted to use something very present, from the now.

I used very random bits — some of them are from Egyptian pop music — but it felt like using the radio was like using the space of the present, especially as radio in Palestine has this power dynamic in the radio frequencies.

Israeli radio stations always interfere with Palestinian radio. One minute you’re listening to a station in Arabic, then something else comes in and it’s in Hebrew. Not to use that specific sound, but something from the Palestinian airwaves, was the goal.

"Palestinians live on collective memory, and the memory of this generation is based on stories of our grandparents leaving their towns and villages"

This seems quite reminiscent of the pirate radio stations that operated in the UK during the 1980s/1990s.

Yeah, absolutely. Another thing from the album was that there is a human voice in every track, even if it isn’t obvious. This kind of introduces another concept of the album, Simya’, which was this ancient spiritual science, a metaphysical science. Kind of like alchemy, not using the elements but numbers and the alphabet. If you make specific patterns, then that can allow you to communicate with the unseen, the spiritual.

There’s not much written about it, especially online. It was an interesting concept for me to try and communicate with my ancestors, to document our history before it is erased.

Palestinians live on collective memory, and the memory of this generation is based on stories of our grandparents leaving their towns and villages. We have this nostalgia to something we’ve never seen or experienced. Simya’ is kind of a method I wanted to use to get these stories.

So you’re using the human voice to conjure this, is that some method of Simya’?

The way I see it, the numbers are the musical elements — the beats, bass, samples and so forth — and then the alphabetical element is represented by the letters.

It’s a really interesting concept in general, Simya’.

Yeah, absolutely. My previous album ‘Inkanakuntu‘, was similar in that it was about reincarnation and summoning resistance fighters — basically our grandparents, who were murdered during the ethnic cleansing of Palestine — reincarnating them, bringing them back to create Palestinan superheroes who make weird electronic music as a form of resistance. The Hundebiss record is kind of a continuation of that.

Can you tell us about the artwork?

The album’s artwork was made by Basel Abbas & Ruanne Abou-Rahme who also did the album artwork for ‘Inkanakuntu‘ LP on Discrepant. In fact, together we are working on a platform called Bilna’es.

However it’s not a record label. It will release music, and it does with Dakn’s release, but it’s more of a hybrid publishing project rather than solely music. It’ll have web projects, publications, and performances as well. It aims to support the artistic community in and beyond Palestine. The idea is to be fluid with who Bilna’es is and what it does.

I think these broader projects are where music is wanting itself to be pushed. Fluid communities with horizontal hierarchy are super interesting. You don’t find this stuff happening in cozy western countries, in a way.

Record labels have become too regimented in their formula. There’s nothing wrong with that, but we personally feel this urgency to do something that’s a lot more broad and open. We work with different forms, especially Basel & Ruanne. They do heavily researched projects, and work a lot with installation art using sound, image, text and objects.

Is there a chance that you’ll do some audio visual work, in collaboration with them?

Yeah, actually we have a performance group called Tashweesh using sound and image. We created a new performance, which we showed in New York in 2019 at the Fisher Center of Bard College. We did the performance inside the installation, as part of it, performing 4 times in 5 days.

"For me to be doing one specific thing defeats the purpose. I have this feeling that I need to try doing different things"

What is it that draws you to these multimodal projects, or artists expanding outside their comfort zones?

I think it’s very important. In Palestine we have an urgency to do many different things in order to survive, you can’t just do one thing. That’s also part of the psychology of how life is today, especially in Palestine.

It’s not easy, you know. We don’t have a music industry. We can’t just make an album and go ‘now I’d better find a label to release this’, it’s not like that. All the musicians I know in Palestine are also sound engineers or technicians for events, and they’re also DJs and producers, and they rap – you know what I mean?

One day they’re doing hip-hop, the next day something else. Mainly because they have all these things in them, but then, just as importantly, they need to do all these things in order to survive, to pay the rent and bills. The more things you do, the more doors open up.

Is that what it’s like for you also?

Yeah, of course, but for me as well as many others making music is my therapy. For me to be doing one specific thing defeats the purpose. I have this feeling that I need to try doing different things. I make music for film, I make music for dance and theatre, I mix other people’s music. I do a lot of these things, not in the commercial sense of doing it for money, but to get the rent in order to survive — in artistic terms, sure, but also in practical ones. That’s all I do — I’m a full-time musician. I can’t just make beats and see what happens.

Do you primarily make music for yourself, or is there a catharsis in releasing and sharing it to others, making it available?

I make music for myself in the moment I am making it. But, of course, it’s important for me to share the music, to create this communication or discussion — that’s just as much a part of the therapy. It’s not one-sided, I’m not just sending through a track and saying ‘listen to this’, but sparking conversation, asking questions and provoking responses.

I would go crazy if I couldn’t make music. That’s happened to me sometimes, when I‘m travelling or I don’t have the right equipment or tools to be making music. It doesn’t feel right, something wrong is happening in my body and my mind. I think I’d go insane without music.

I started making music on a daily basis during the 22-day curfew that happened in Palestine in 2002 or 2003. We were living under curfew or house arrest for 22 days straight, and the only way to survive that, mentally, was to make music.

Thankfully we had a computer in the house, and I had some pirated software and during that time the only way to stay sane was to make music the whole time. It was a very traumatic phase or time of my life. If you looked out the window, you could get shot. There were tanks, the Israeli army was everywhere.

Was that your entire neighbourhood?

The entire West Bank was under house arrest. Some people died in their homes because they needed specific medication, others died from lack of food. Of course neighbours were sharing, but you have old, single people living alone at home, or those needing their prescription.

A lot of the time there were periods where there was no electricity, and I couldn’t make music then, but you get the idea. Producing music certainly saved me. I still feel that today. This is my way of surviving. That’s what I mean by therapeutic.

It’s hard to imagine, and quite an interesting parallel – or not quite – with the lockdown now. The situation with COVID-19 in Palestine seems typically difficult. I saw news posts about Israeli soldiers destroying supplied aid and water at checkpoints, stopping people from providing medical aid.

Yeah, I’m in Berlin, but from what I’ve heard from my family and friends, since the beginning of the pandemic we’ve seen videos of volunteers standing outside villages, towns and small cities, wearing face masks and giving out hand sanitiser and documents that spread awareness of COVID-19 telling people to be careful and practice social distancing.

Those volunteers were arrested by the Israeli army and the Israeli Police for no apparent reason. I mean what other reason could there be, that they want us to get the virus?

The volunteers were Israeli, or Palestinian?

Palestinian. But, there might have been this fear of the community coming to exist again in Palestine, like it did before. A community working together, helping each other, would give a sense of hope that the authority forces did not want. That is the only analysis that makes sense to me, because otherwise they just want us to get the virus and die, which also makes sense. You can see that now with what’s happening with the vaccine.

All of a sudden, Israel is the most vaccinated country in the world, and Palestinians haven’t received a single vaccine to date. They’re going around international law, saying that Palestinians are responsible for their own medical treatment, which is complete bullshit. They’re the occupying power, the colonisers, who run the borders.

You don’t just get vaccines in the mail, they have to be transported in specific ways, under specific conditions, and they’re very easily damaged. So it’s complete bullshit to push control of the vaccination onto us. They just don’t want the responsibility, but they want to be the top country for vaccination to promote Israel to other countries.

It is really sickening.

Yeah, it’s a genocide. We have 2000 deaths and for our small population, that’s a lot. You see news about outbreaks every other day and Gaza has a very dense population.

I saw an article from September saying deaths were at around the 200 mark.

Yeah, it’s gone up a lot since. I think the BBC reported on it recently with updated numbers, something like 175,000 infected and 2,000 deaths.

I’ve found the article. Fatality rate in OPTs (Occupied Palestinian Territories) is 1.1%, in Israel it’s 0.7%.

Another really important thing is the 5000 and something Palestinian political prisoners in Israeli jails. They’re refusing to allow social distancing, refusing to give them face masks, not allowing higher hygiene standards. So, they’re basically killing them. There’s already cases inside the prisons for Palestinians, and they can’t save themselves from it.

And the jails are annexed, right, you don’t have Palestinians mixing with Israelis here?

Yeah, they’re administrative prisons. They don’t have a court date, they’re just there until further notice, which is also illegal. And now they have no protection against COVID-19.

Also, the Palestinian government cannot subsidise anything. It lives off international funding, and it cannot help the small businesses which are being forced to shut down as they cannot survive, from the first lockdown to now, as well as the workers who were laid off. It’s killing the community. The only ones that will survive are the international corporations.

That is possibly the only similarity between our different worlds. I have seen this and heard of it happening here in the west.

There’s no funding like there is in Germany, artists receiving huge sums of money because they lost their work. Small businesses in Germany get 70% of what they made last year, just so they can survive. Small restaurants and shops are getting some sort of funding, because they had to shut down.

In Palestine you get nothing. And there’s the occupiers’ restrictions on top of the COVID-19 restrictions. The international aid that the Palestinian authorities used to rely on don’t have the means to continue that aid, or choose not to give it. I mean, it’s not like we see any of that aid anyway, the government keeps it all.

Also, we’re not able to produce for ourselves in factories. They get shut down by Israel every time we try, which is why we have this urgency to produce what we can, music or art, that they cannot shut down.

‘Kamil Manqus’ is out now via Hundebiss Records. Order a copy from Bandcamp.

TRACKLIST

1. Quboor Mamila

2. Shay’an Fa Shay’an

3. Simya’

4. Bilharf Alwahad

5. Ma Wara’

6. Dirasat ‘Ulya

7. Tanqeeb

8. Ikmal