Inverted Audio has partnered with REMAIIN (Radical Electronic Music and its Intercultural Nature), a project investigating non-European cultural influences on experimental and avant-garde music of the present and past.

During the partnership, Inverted Audio will feature and host interviews, essays, mixes and news from and featuring the REMAIIN team and the work they are doing in highlighting the importance of intercultural exchange in advancing music and sonic art.

This essay, written by Japanese musician and clarinet specialist Michiko Ogawa, describes Teiji Ito‘s journey in music and outlines his understanding of the world through the lens of his spiritual development and interest in voodoo and it’s connection with the “primitive animism” aspects of Japanese Shinto theology.

Ogawa’s investigations, undertaken in step with a project based on transcribing some of Teiji Ito’s notable original works (commissioned for Kontraklang Festival), detail an artist superbly capable of blending their cultural heritage with the avant-garde.

We are pleased to be featuring this essay to Teiji Ito, a foundational artist in his field of music, and hope that readers find Ogawa’s writing and the story of Ito’s life a source of inspiration in their own life or musical practice.

Essay by Michiko Ogawa

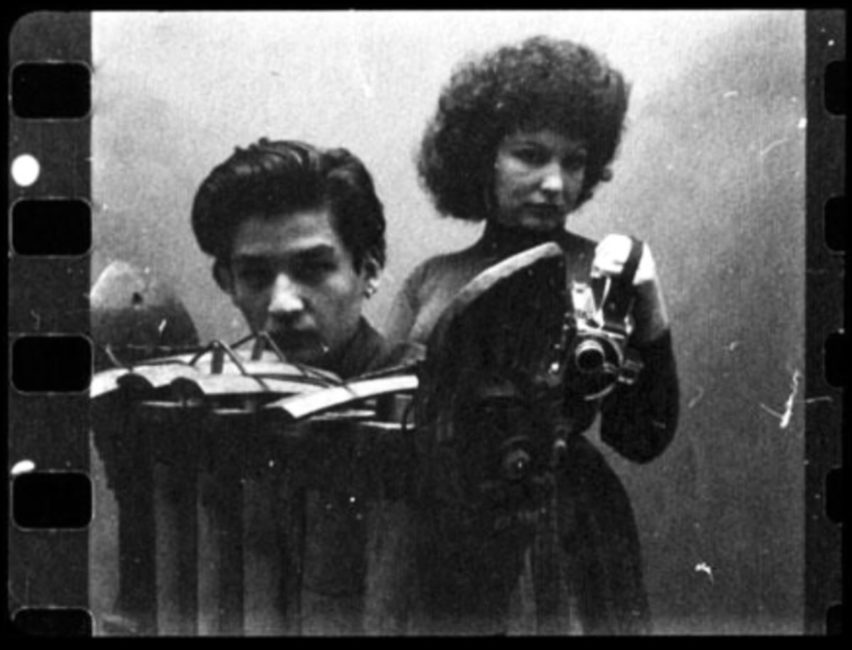

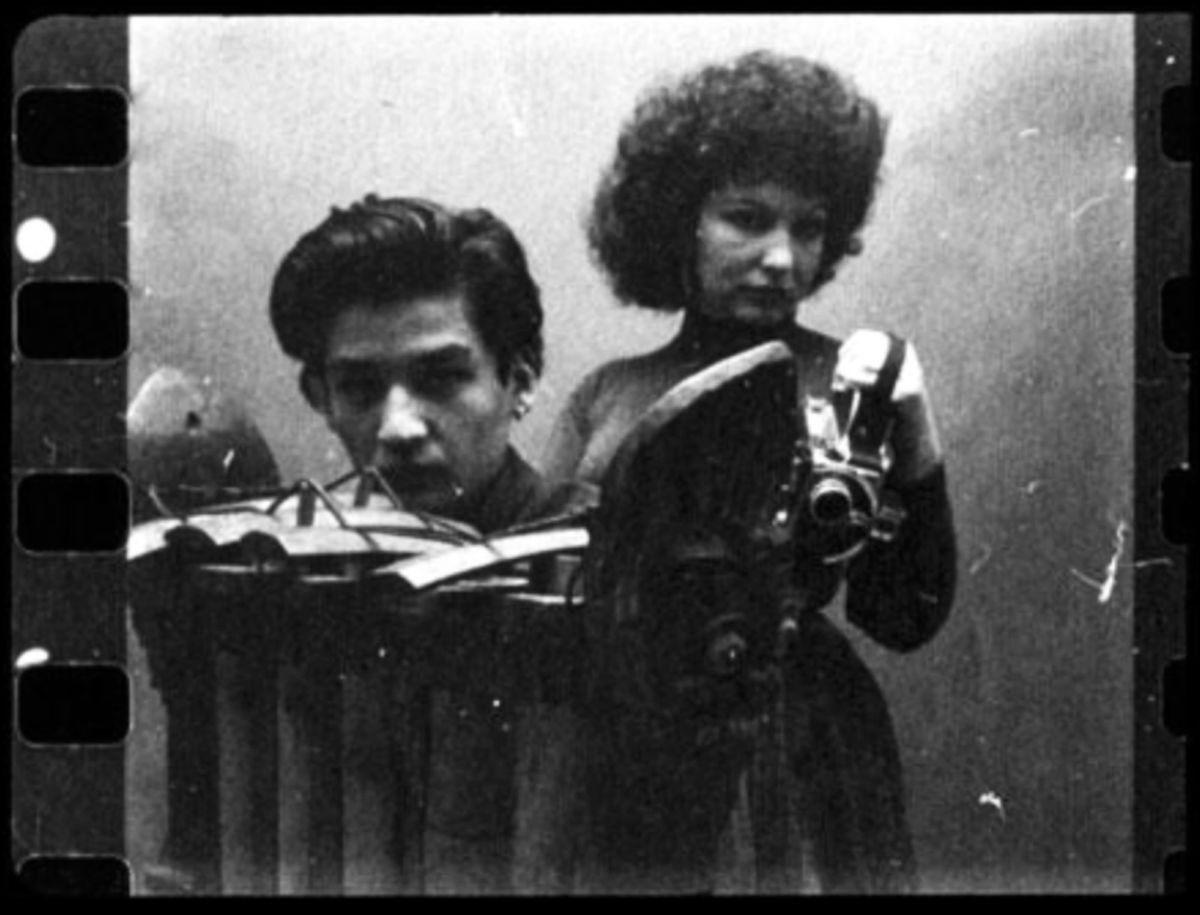

His career as a composer and performer radically accelerated after creating the soundtrack to Deren’s 1958 film ‘The Very Eye of Night‘, culminating in the creation of Ito’s incredible and iconic score to Deren’s best known film, ‘Meshes of the Afternoon‘ (which he composed 16 years after the film was made). Much of Ito’s work was not rigorously scored to paper, but rather driven by a set of guiding ideas that would be collected and later recorded directly to multi-track tape.

I have transcribed Ito’s original recordings in detail and assembled a group of musicians to realise a live performance of six of Ito’s most well-known film scores for Maya Deren and Marie Menken, set to 16mm prints.

This project was premiered at the Brisbane International Film Festival 2018, and the European premiere was organised by Kontraklang Festival as a part of the REMAIIN project in March 2021.

As COVID-19 restrictions made this project impossible, I created a film in collaboration with Manuel Lima exploring many of the key themes of Ito’s working process, however I would also like to take this opportunity to write here some more historically grounded information about Teiji Ito’s life and work.

AN ITINERANT LIFE

Teiji Ito was born in Tokyo. His family was full of internationally respected artists. His grandfather, Tamekichi Ito, was an architect and inventor; his uncle Michio Ito was a charismatic dancer, choreographer, and theatre director who performed throughout Germany, England and the USA. Teiji’s father Yuji was an opera singer and costume designer, his mother Teiko was a Japanese-American dancer. There were many other artists beyond these as well. It’s interesting to note that their family traveled extensively overseas, even in the late 19th century. You could say that the family were kind of prototypical cosmopolitans. In 1941, when Teiji was 6 years old, he moved to New York with his parents.

Although world affairs were very strict at that time, they were doubtless looking for an environment that was less repressive than Imperial Japan where they could continue their artistic work. This travel was made possible because Teiji’s mother Teiko was a U.S citizen. Yet after Pearl Harbour in 1942, the US Government began to enforce a policy of internment for Japanese civilians. According to Tavia Ito (the daughter of Teiji Ito and Maya Deren), they were able to escape this by pretending to be South-Korean, changing their name from “Ito” to “Ko”. This modification came from their mother’s name, changing “Teiko” to “Tei-Ko”. It sounds unbelievable, but it worked, and the family remained “Ko” until the early 1950s, when they were finally able to change back.

Teiji was a musical genius, and his daughter Tavia said of him “he was born as music.” Even at age 5 he was performing drums as part of his mother’s dance recitals. He was accepted to the High School of Music and Art in NYC, he received classical training as a clarinetist. But within a year he dropped out of school and ran away from his parents. According to Tavia, Teiji was always very proud of this decision. Afterwards, while Teiji was living homeless (either sleeping in the park or a closed movie theatre), he encountered Maya Deren, and the two quickly formed a romantic relationship. After a while, Teiji moved in with her, and they eventually married in 1960, just one year before Maya’s sudden death.

Teiji established his career as a performer-composer in the New York theatre scene and worked for a wide variety of projects including off Broadway, NY City Ballet, La MaMa among others and toured all over the world until his sudden passing at age 47 from a heart attack in 1982 (while he was in Haiti, where his body was buried).

SPIRITUAL JOURNEY

Ito’s encounter with Maya Deren brought not only artistic opportunities, but also a significant spiritual component into his life: namely voodoo. Maya was already deeply initiated to this world: she was a Voodoo priest when they met. When Teiji and Maya started living together, they began to share everything in life, including Maya’s strong interest in voodoo, for which they traveled together to Haiti several times. There, Teiji learned Haitian Drums from an indigenous Haitian drum master.

Teiji had suffered from the exposure to Catholic dogma he received throughout his early life (particularly in relation to schooling). This was one of the reasons why he ran away from his parents’ house and dropped out of high school. Amongst the materials in the Teiji Ito collection at the New York Public Library, I found the following note written by Teiji describing how sensational his first encounter with voodoo was:

“After 10 years of Catholic Dogma through elementary and high school, I found myself unable to understand or relate to the world around me. At the age sixteen, I was biologically and soulful ready to find out “what is happening” because as far as I was concerned, it wasn’t happening at school, at home, on the way to both, nor on Saturday or Sunday, at church, movies, or on the street.

To me it was happening at the Waldorf cafeteria on Sixth Ave. and 8th St. Between the hours of 8PM and 5:30AM. There I met the Ghedes (Haitian Voodoo God of life and death) and the Legbas (Voudoo deity) that are around, and one does meet if you are looking. The bum with the incredible sense of humour and survival. The old bums who you feel “really know” in the park- meeting and talking together, sharing the bottle of wine- and a “queen of the bums” elegantly offering cigarette butts from a battered Du Mauriere tin. And in the park, the young and penniless and not so penniless poets, painters, musicians and dancers, cops, quack doctors, teachers and spaced-out handymen. Style – Honesty – Truth – Justice – search for love – freedom from boredom – meals – a place to sleep. It was all important. But where does it fit? Where are they at? Why is it important?

Looking for rituals – protective talismans – initiations into adult life… I met a priest and was introduced to the first print Legba, Keeper of the Gates to the Underworld, the threshold to the other world. Through him the rituals will be performed.”

Teiji Ito, “Teiji Ito – Random note”, typed by C.Ito, Teiji Ito collections (New York, NYPL; date unknown)

One of the reasons that voodoo must have seemed appealing to Teiji at this time may have been because of his complex cultural background. Japan is a country that has maintained different kinds of belief systems, which coexist in harmony. Many different religions are practiced in Japan including Shinto, Buddhism, various folk religions (such as shugen-dō and the Ryukyuan religion), and Christianity, without any conflicts.

That is because underlying everything is a deep sense of animism. It is said that there are as many as 8 million gods from the ancient times in Japan. These gods have come from nature, non-existent creatures or figures in ancient myth, persons passed away, and animals such as foxes or cows among others. In some places, such as Okinawa or the Tōhoku region, a primitive animism is still practiced today as the main belief.

People in these places will still visit a shaman to ask questions, and sometimes try to hear the voice of someone who already passed away speaking through the shaman (a form of possession). The system of religious beliefs and life-styles in Japan are also deeply rooted in the strong tradition of indigenous religions, in which possession plays an important role, and all this is maintained despite all the changes that have occurred through modernisation/industrialisation.

This, Japan has in common with Haiti, which is also an island culture when many cultural influences have mixed and come together to form something new. Although Teiji spent his most impressionable years at the Catholic school in New York, he felt that he had gotten lost by the time he was 15 years old. Coming across voodoo and the people around it changed his life, in a way that significantly still incorporated certain elements of Catholicism, alongside primitive animism.

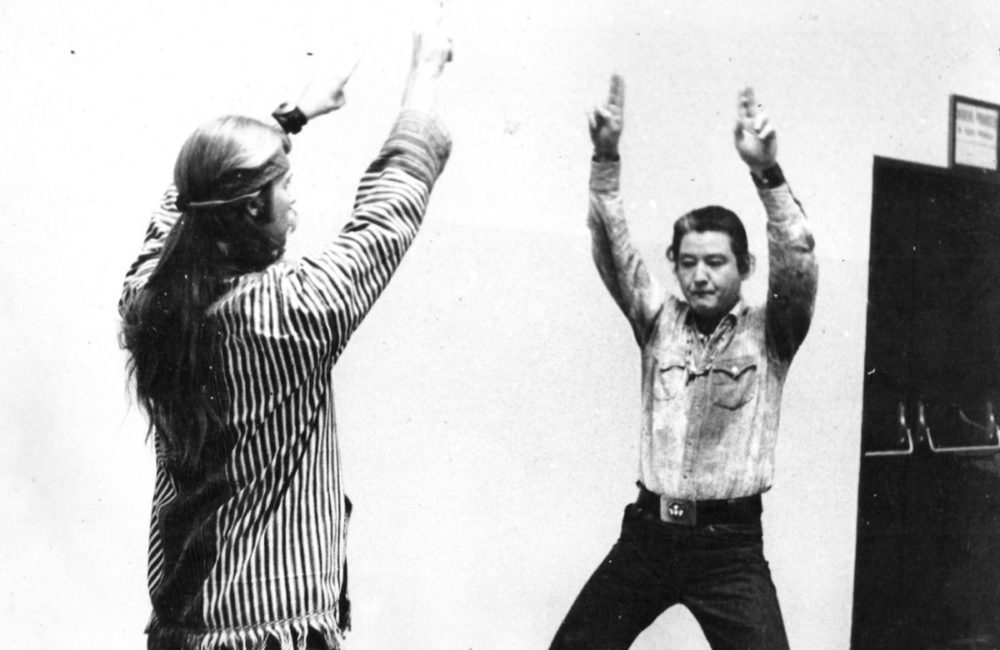

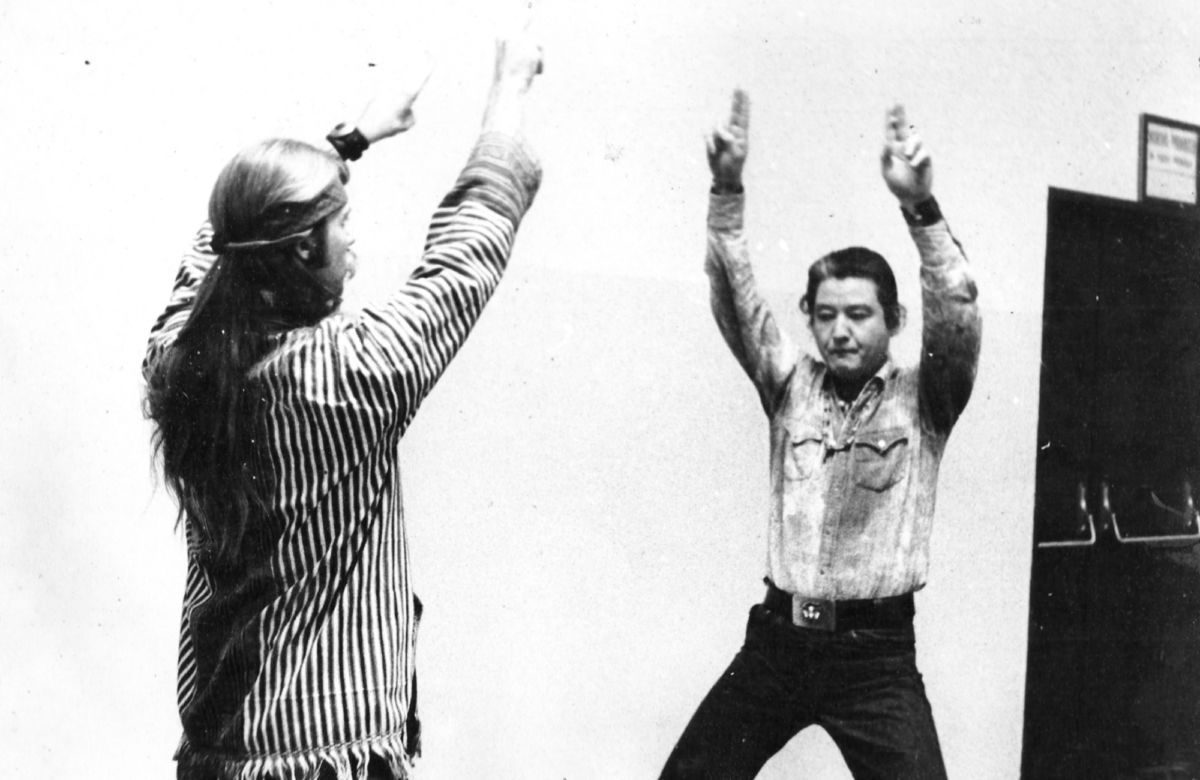

Therefore, voodoo might have been the perfect catalyst for Teiji since in it he could see both sides of Japan and America, East and West. This encounter opened his spirit up to the world and to the cosmos. Another aspect of voodoo that appealed to Maya and Teiji was the significance of ritual, ceremony, and trance. Several associates, including Barbara Pollitt, have noted that Ito seemed to be in a trance-like state when making music.

Working at the dawn of the New Age movement through the 1960s and 1970s, Teiji’s interest in a wide variety of religious and mystical practices, together with a belief that music must play a “healing” role in society, was very much constant with the spirit of his time. He saw himself as something of a shaman, and in my interviews with his collaborators Teiji’s insistence that his music be understood as part of something larger, deeper, cosmic, in harmony with the whole universe, was clear.

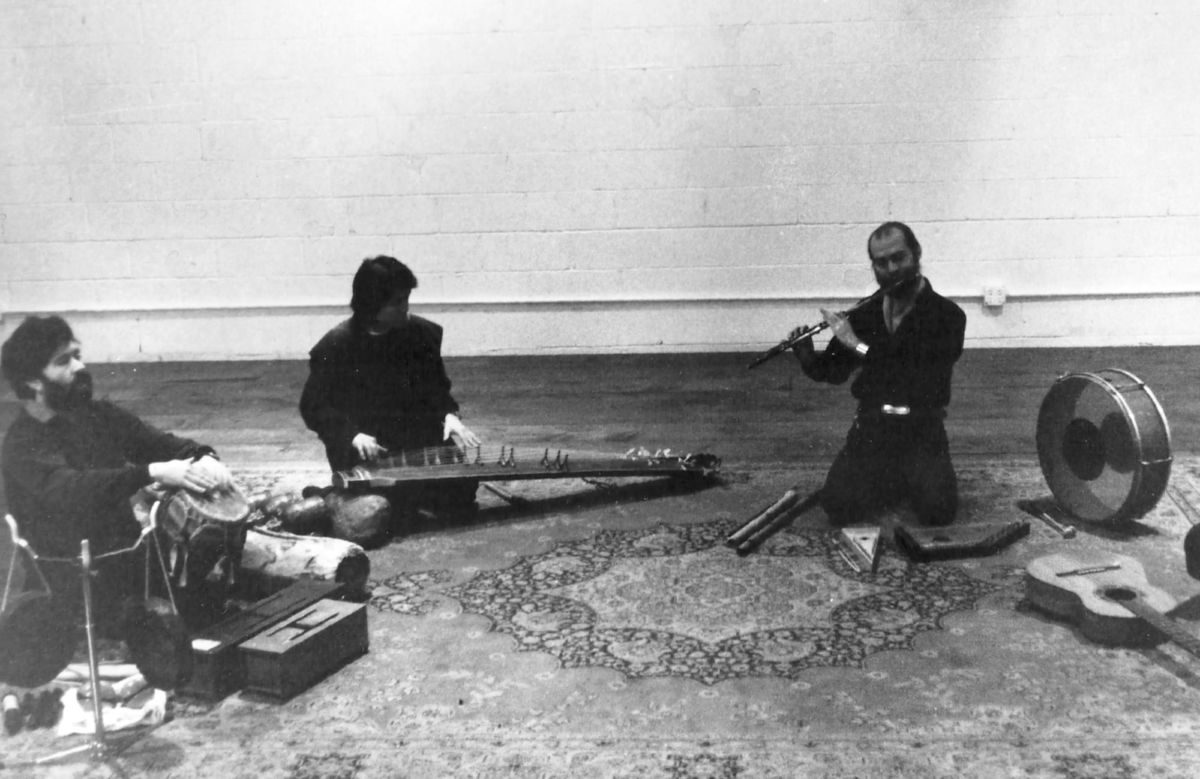

1001 INSTRUMENTS

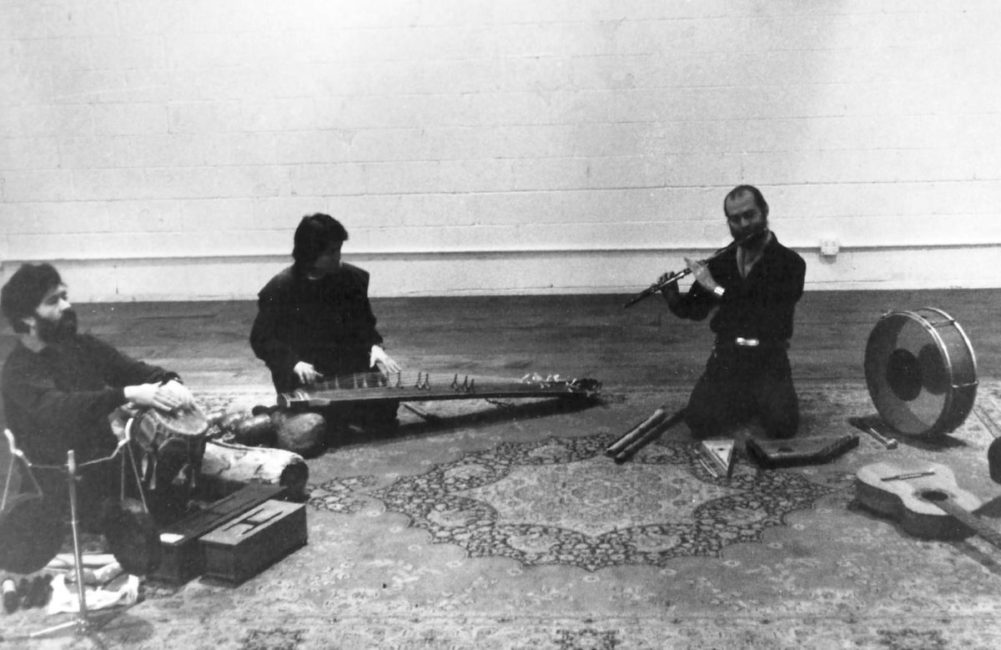

Teiji had a great number of instruments in his collection. Some of his Japanese instruments were inherited from his family or purchased on his trips back there, Maya brought Caribbean drums back from Haiti, African and Indian instruments were given to him by friends, and some were discovered through diligent search or happenstance in obscure corners of pawn shops. Ito felt most of his instruments to be irreplaceable: most of the indigenous instruments were nearly impossible to find, and even the more standard western instruments had been carefully selected. So Teiji brought his own instruments with him when he toured.

A very revealing point is that he almost never bought brand new instruments from strangers: he collected most of his instruments though family, relatives, friends, and sourced them second-hand, etc. He enjoyed getting to know each instrument whilst respecting its individual characteristics, spending a long time with each one at home.

Teiji felt that an instrument’s history and story were an important part of its life, and thus each was one-of-a-kind. He even constructed a drum himself from a fresh deer skin given to him by a friend who worked in a restaurant; this drum was used extensively in his last work ‘Axis Mundi‘. Teiji believed that by making it himself, a part of himself could dwell within the instrument. Clearly, Teiji felt a deep bodily connection to the instruments that he played: they were a connection between himself and the world at large, a connection with friends, family, and ancestors, that he felt on both a mental and physical level.

Teiji was fluent in a wide variety of musical styles, such as flamenco guitar, western classical music, Portuguese fado guitar, Jazz drumming, various styles of Japanese flute music including shakuhachi, and Irish flute, among others. He was also renowned for his gorgeous voice, and later in life became interested in Native American singing.

Many, but not all, of the above were self-taught from quite a young age. He was able to understand complicated polyrhythms, nuances of intonation, harmony, scales and musical structures, all of which was brought to his own music in a very original and elegant way. This was enabled by his having a very conventionally strict musical education from a young age, and of course a special gift for music, together with a free and inquisitive spirit.

It is very rare that a teenager of only 15 years old already has their own clear vision of art, and Teiji was indeed a rare person. He had an extremely clear view of what he did and didn’t want out of life, of his artistic vision, already at this young age. To illustrate Teiji’s musical outlook through looking at his learning process, consider the following anecdote from his friend Guy Kulcevsek:

“A good story about how he learned to play instruments: he asked me once if he could play my accordion. I said sure, and handed to him, and started to tell him how the buttons were arranged in the bass. “I don’t want to know that” he said. He didn’t learn like a classical musician, by mastering rudiments of scales, etc., he learned by feel, the way a child learns language. He wanted to make music, not learn technique.”

Email interview with Guy Klucevsek (April 16th, 2017)

GROUNDED IN THE UNIVERSE

Throughout his life, Teiji never lost his sense of pure curiosity, nor his view that through musical exploration he could develop a deeper connection with the cosmos. He used his own instruments freely, in a way that was unique to him, developed through years of concentrated engagement. He was always keen to take on new musical ideas and influences, integrating them into his unique artistic vision, and used recording technology to further develop his stylistically syncretic works.

Teiji’s working process somehow reminds me of seeing my own daughter’s attitude towards play: objects are filled with potential, and each has no set or specific purpose. There is no “right” or “wrong,” only a growing body of knowledge formed by repeatedly asking “what if?” Objects are recombined in an infinite number of new and interesting ways, calling to mind Levi-Strauss’s discussion of “Bricolage” as outlined in ‘The Savage Mind‘ (1962).

One of the things that strikes me the most about Ito’s music was his talent for cultural syncretism, as he worked to incorporate various musical traditions into his music like a collage, but with the whole never turning into a variety show.

He spoke so clearly with his own voice. I feel that this comes from his deep physical connection to his instruments, and the knowledge he generated through his engagement with them as a performer. Music for him was never about systems or patterns to be decoded with logic, but something that was embodied and felt. This allowed his own spirit and joy to shine through regardless of the musical material he was using.

It is a shame that sometimes Ito’s work gets lumped into categories of “world” or “new age” music. This classification may be understandable in as much as his work was deeply syncretic and referenced a wide range of traditions and cultures, however his work never strayed into the direction of cultural appropriation, and his spirituality was something deeply felt and rigorously developed.

For me, I feel that Teiji points a way forward for the future: in his work multiple influences and practices coexist in harmony, treated with respect and tenderness, in a way that was deeply meaningful on a personal level and grounded in a clear and direct physical relationship between body and instrument.

Inverted Audio is an official media partner of REMAIIN. Stay tuned for further news articles and features.