In Part 1 of this review we outlined the initial three days of Prague’s Lunchmeat Festival, detailing the first round of events and the conditions that the festival was operated under in order to run during Coronavirus restrictions. Part 2 covers the festival itself: the final three days of performances.

The audience are somewhat reeling after the mind-numbing sensation of NONOTAK. The high of the event buzzes around our ears, combining with the excitement of knowing the festival will go ahead tomorrow. None of us knew what to expect: would this be three days of feeling subjugated by restrictions and security, or would we enjoy a freedom that some hadn’t experienced in months?

The answer was far closer to the latter of the two, and whilst restrictions were there, the festival was an explosion of pent-up creativity. There were, of course, restrictions, but the bar’s 10pm curfew seemed to result in a more engaged audience, the limitations on capacity granting more room to dance. Sure, dancing with a mask on isn’t the best fun, but there’s no logic in complaining when it’s the key to nightlife.

Like all the best festivals, the last three days of Lunchmeat are an analogous passage in time. Whilst each individual act was memorable, the chronology becomes unimportant in hindsight, even inhibiting the flow of memory.

What can be said, however, was that there were definite trends within those days: Prague’s local musicians were enthralling, and showed a level of dedication to creating new art that is hard to come by; Lunchmeat Festival showed their class, supplying the audience with stunning performances despite seeming to be fighting against the fates themselves; and of course, the headline acts showed just why they are celebrated as such with shiver-inducing performances.

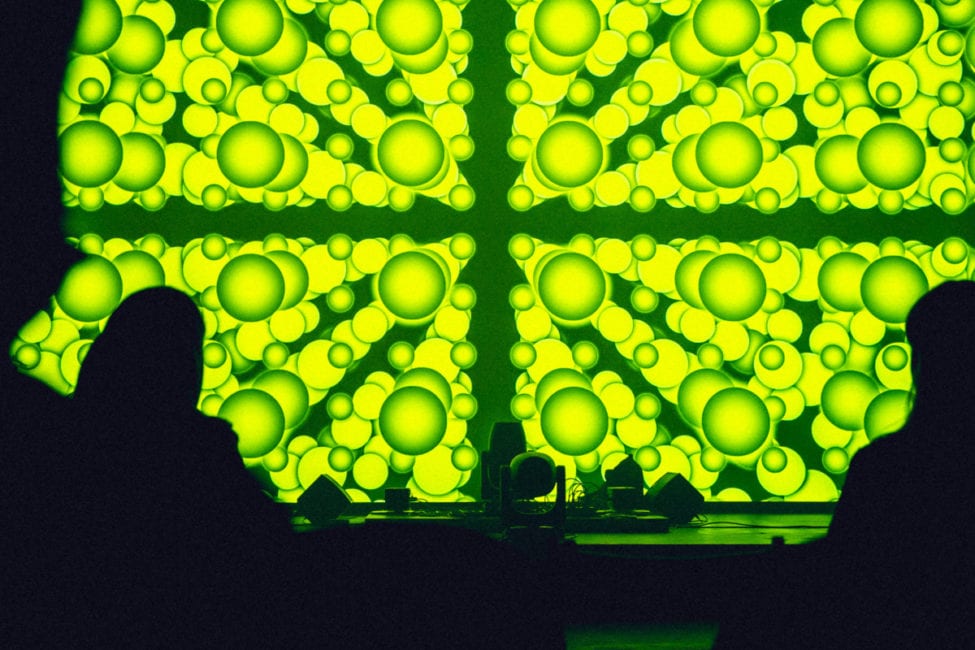

Awaiting our arrival on the first day is a screen in the festival’s vivid green livery. Very shortly, the “Sensory Test”, which prefaces the performances each evening, begins. Created by Lunchmeat Festival’s Gabriela Prochazka, it stands as an emblem for Lunchmeat’s diversity in approach and strength of concept realisation.

"A whirlwind of emotions from beginning to end, Lunchmeat impressed immensely — primarily for the dedication of its team, but also the exceptional local artists who showed their colours"

The short clip puts you through your paces of perception, from frequency response to optical illusions, the application of sound theory embellishing the experience with an almost academic feel — even closer to the mark, like an experimental psychological test from the ’60’s. This was compounded by the mischievous robotic voice which guided you through, providing fair warning that the frequencies and visual chaos might well induce faintness and nausea.

We’re slowly immersed in a sound bath of resonant frequencies that instilled emotions as unassuming as lethargy (01hz Delta wave) and as physically impactful as fear (32hz Beta wave). Illusory spirals plunge into a heavy breakbeat mayhem that shook any un-seated chairs into disarray. Dazed applause is about all that can be mustered from the reeling participants.

Stanislav Abrahám starts shortly after. Beginning with an extended effects-laden gong sound bath, he takes his time soothing the audience into hypnosis with the ancient instrument, taking the edge off the high-intensity sense test. With a certain amount of calm instilled, Stanislav then steps to a more “traditional” electronic set-up, and proceeds to guide us into smooth ambient territory, rich in textured crackles and pacifying drone.

After this, we’re directed upstairs to the ‘Club’ stage, which I’m told in past editions becomes the cradle for some of the festival’s most vibrant hedonism. The stage, a room made behind the control panel of the main auditorium, features no seating, and whilst small there is plenty of room to be suitably spaced.

Toyota Vangelis opens the stage. Something of a local prodigy, Prague natives tell me how each performance is unlike the others. For this performance, we’re played a surprisingly compatible combination of trance and R&B, soft lyrics and autotune, weaving around ecstatic melodies mostly disassociated from the peak hour energy that “trance” immediately brings to mind.

Afterwards, we swiftly head back to our seats for the first international act: Northern Electronics’ Anthony Linell and renowned visual artist Ali M. Demirel presenting ‘Winter Ashes‘ live A/V. Borne from a long-standing admiration of Ali’s visuals for Richie Hawtin/Plastikman and others, for ‘Winter Ashes‘ Linell combines his talents in making austere and bleak music with Demirel’s footage of Iceland’s most inaccessible and otherworldly landscapes to create a silent narrative reflecting on ancient Norse myth.

The performance is a passport not only to Iceland’s unique shores, but something more alien than even the isolated isle is capable of placing in our minds. To describe it as a perfect match would slightly undersell the apparent synchronicity between the two. Linell paints with sound images just as eloquent as Demirel’s stunning videography, the senses of sight and sound merging into a singular whole.

This seems to be achieved in several ways, not the least of which is the pair’s approach to focus and scale. As Linell zooms in on a particular sequence, intensifying the density and colour of sound, Demirel scopes out until grand, sheer cliffs appear out of fog; when Demirel’s attention is reduced to a tiny pool of hot, bubbling mud, Linell sounds massive and imposing.

"Linell paints with sound images just as eloquent as Demirel's stunning videography, the senses of sight and sound merging into a singular whole"

In this way the pair narrate a common truth in nature: that the grandest designs of nature are often present at the greatest and smallest of scales at the same time. With ‘Winter Ashes‘, the great and the small became so intrinsically linked that there can be no aesthetic separation. It leaves the raptured audience with a conflicted parting emotion of having witnessed something quietly monumental — and in that, they certainly communicate a taste of Norse legend.

After a heady first day of A/V-centric acts, it was quite comforting to see the main stage illuminated by a small desk light only for Shackleton, who closed the first day with unshackled dance music, bursting with energy and power.

The speakers, pushed harder and louder than for previous acts, seemed to want his music to be played so destructively, to the point that the ground seems almost liquidated. The air feels close, the atmosphere collected and unified, the wild, limb-thrashing dancing of the crowd the perfect image of catharsis, which Shackleton latched onto and increased almost exponentially.

It’s telling of an artist’s capabilities that they can operate on the limits of expectations for such a long time and still elude generic classifications. By contrast, it seems so easy to understand, so evocative it is of the early functions of music — to unify all in a celebration of life, and of being alive.

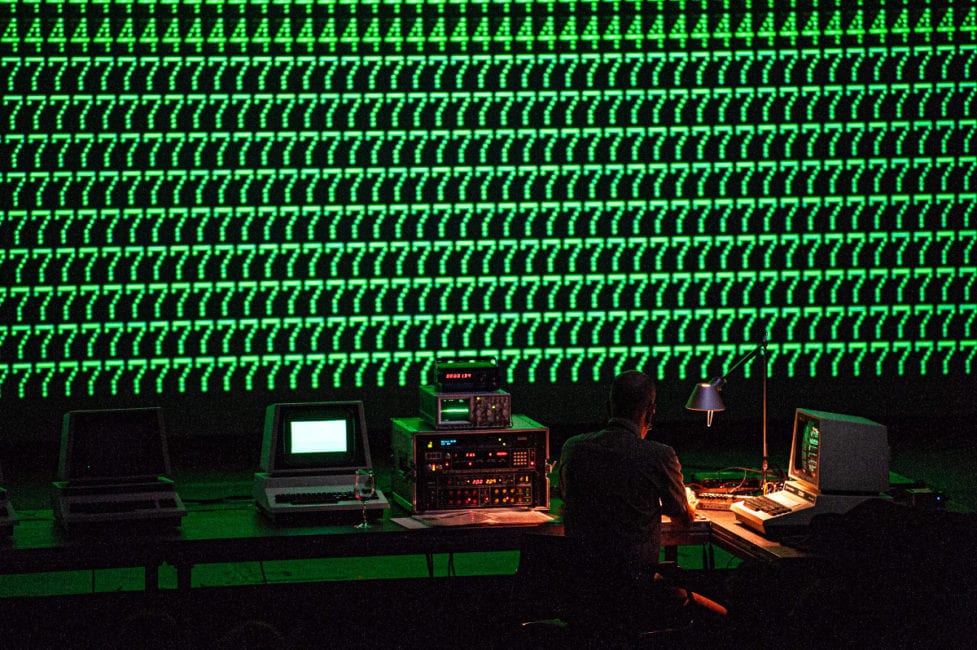

All throughout the festival I’m drip-fed pockets of gossip of the drama behind the scenes, including one 1,000+ mile drive to Prague. The opening act on the second day was one such tale. After driving to Berlin to pick up Robert Henke‘s CBM computers for his live performance, the van broke down. A fairly punishing deadline was given, and scarce moments before it arrived a favour was pulled in to bring the machines to Prague on time.

Thank the fates that it happened, as Henke’s CBM 8032 A/V project was one of the most exhilarating performances of the festival. After the first day, the air is more relaxed inside the auditorium, perhaps instilled by the welcoming scene of Henke sitting on the corner of the stage like a professor awaiting class.

We learn that the CBM 8032 was the first socially democratic computer, many hundreds of dollars cheaper than the next available product on the market 40 years ago. The product allowed for rudimentary music making and visual design creation, but only within hard limits, such as the fact only one note per computer can be played at a time.

Years in the making, the final performance is facilitated by three computers producing the notes, the custom-modification of one CBM into a sequencer, and one final computer for visuals, using only a smattering of several hundred symbols. Further alteration to the audio is added using the era’s hardware.

"Henke's performance was a tour-de-force of how to create true art under positively mind-numbing restrictions — a nice metaphor for the festival itself"

Somehow, despite all of the technical impossibilities, Henke’s performance was a tour-de-force of how to create true art under positively mind-numbing restrictions — a nice metaphor for the festival itself.

For 40 minutes we’re bathed in dizzying patterns that frankly defy thorough inspection, all rendered in the green glow of early computers. One has just vague notions of the amount of time taken to create the visual works alone. The music, too, seemed like the realisation of an impossibility: thundering techno, tense, crackling interludes, and astonishing sound design… all and more were pulled off with a stern aestheticism that spoke of familiarity and deep-seated love between man and machine.

Nina Pixel, a Czech native now Berlin-based, takes over on the Club stage. Her performance with filmmaker Adrián Kriška, ‘Ancestral Archeologies‘, is one of the most relevant and arresting performances of the festival. A kind of idealised retrospective, the project aims to provide a platform for Queer and Feminist narrative within Slavic folklore.

It’s a touching performance, with simplistic camera footage displaying a small group of LGBTQ+ actors moving and posing to a blurry soundtrack as the seasons revolve. The homely nature of the visual art marries perfectly with the idea of creating a folklore for modern times — these tales are the ones told to us in our homes, after all, by our family members by the peace of a fire in winter.

In the intricate performance, Nina and her cohort of actors make a tangible mark in the wall of ancient myth traditionally reserved for heteronormative storytelling. It’s a subtle demonstration of what can be done to preserve and enshrine LGBTQ+ identity in history. The juxtaposition of placing modern reality inside historical, shared fictions is a powerful tool, deployed here with a tenderness that denotes genuine care.

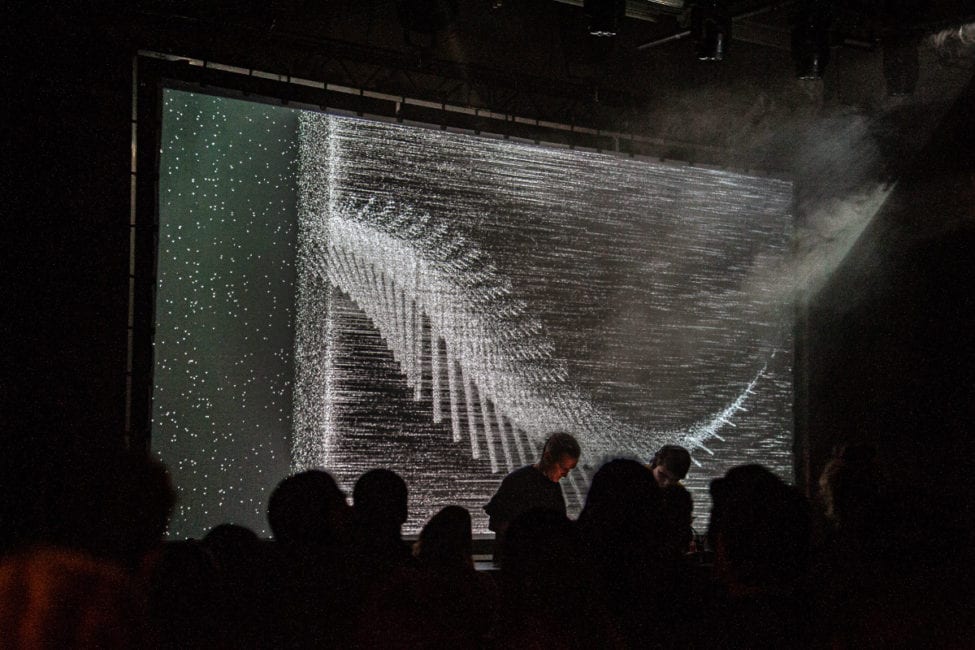

Maenad Veyl’s unfortunate absence turned into a story of sheer heroics from Prague local Exhausted Modern, who woke up that morning to a text from Veyl explaining how he’d be playing live on the main stage later that day. Perhaps being compatible with Veyl’s artistic vision thanks to his release on Veyl Recordings, Exhausted Modern gelled so perfectly with Geso’s discoloured and dystopian imagery that it seemed impossible it was pieced together so fast, with little or no rehearsal time.

The visuals, pallid and haunting, seemed to almost spring from Modern’s music. As the dystopia intensifies, new vistas open before us, like flowers blooming for the sun. Time seems to stretch into infinity before the spectacle, and we find ourselves lost in the magic that binds the performance together.

Regrettably, Helena Hauff was unable to make the travel from Germany. It’s a huge disappointment, although somewhat unsurprising, but before even a syllable of complaint can be uttered, we’re informed DJ Stingray will take the reins for the second evening. Suffice to say the disappointment was short-lived.

"Stingray tore a new roof in the National Gallery that night, with the charismatic artist stoking an already raging fire with tinder-dry fuel and kerosene: ruthless combinations of techno and electro"

Most of what can be said about DJ Stingray has already been said, and while there’s obviously ample room for further praise, sometimes adding to the noise reduces the value of what’s being said. Needless to say, then, that Stingray tore a new roof in the National Gallery that night, with the charismatic artist stoking an already raging fire with tinder-dry fuel and kerosene: ruthless combinations of techno and electro.

The last day opened at the Club stage: suspended front and centre, an angled glass screen carries the image of Nivva — a computer-generated performer who twirls and dances like an early MTV superstar through green screen worlds as her creators, black-robed musicians shirking attention, provide a high-gloss soundtrack.

Nivva stands perhaps as one of the most inimitable and arresting performances of the festival, and the packed room attests to the ingenuity of the act. It’s a strange thing to see a hallmark of futurism lifted from films such as Bladerunner, and although the act is clearly a digital one, the mind begins to wonder how long it’ll be before Nivva is inseparable from a flesh and blood act.

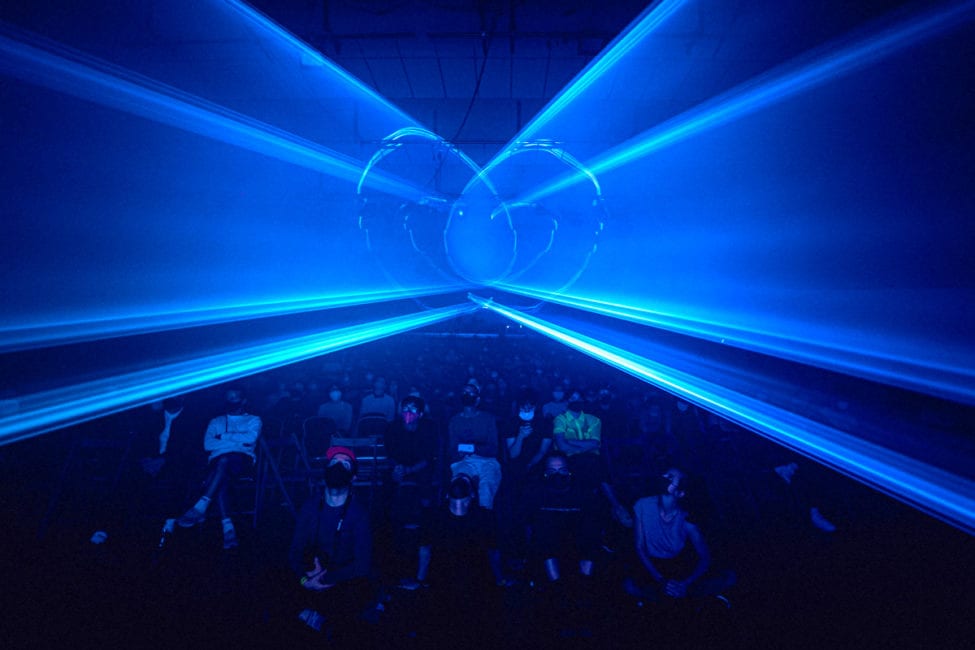

On the main stage, Tadej Droljc follows with ‘Žarkolom Part 2‘, a performance of gritty noise music performed in the centre of a four-way projection spectacle. Firing lasers into sawn segments of industrial ventilation piping, Droljc’s visual art is tactile and tangible, a perfect counterpoint to Nivva’s ethereal nature.

A projection behind Droljc shows artistic videography distilled from studio work of the project flickering behind, as the lasers do their work in real time on the right and left, the beams ricocheting around silver tunnels before glancing out of the trap and into the air.

Droljc’s genius stroke sits on the other side of the stage, though: he uses the entire auditorium as his canvas, blasting light onto the areas of the venue which are ordinarily ignored throughout any performance. Whilst there is certainly something to be appreciated in the light show seen by looking directly at the performer, eyes wandering over the ceiling and walls appreciate the full performance.

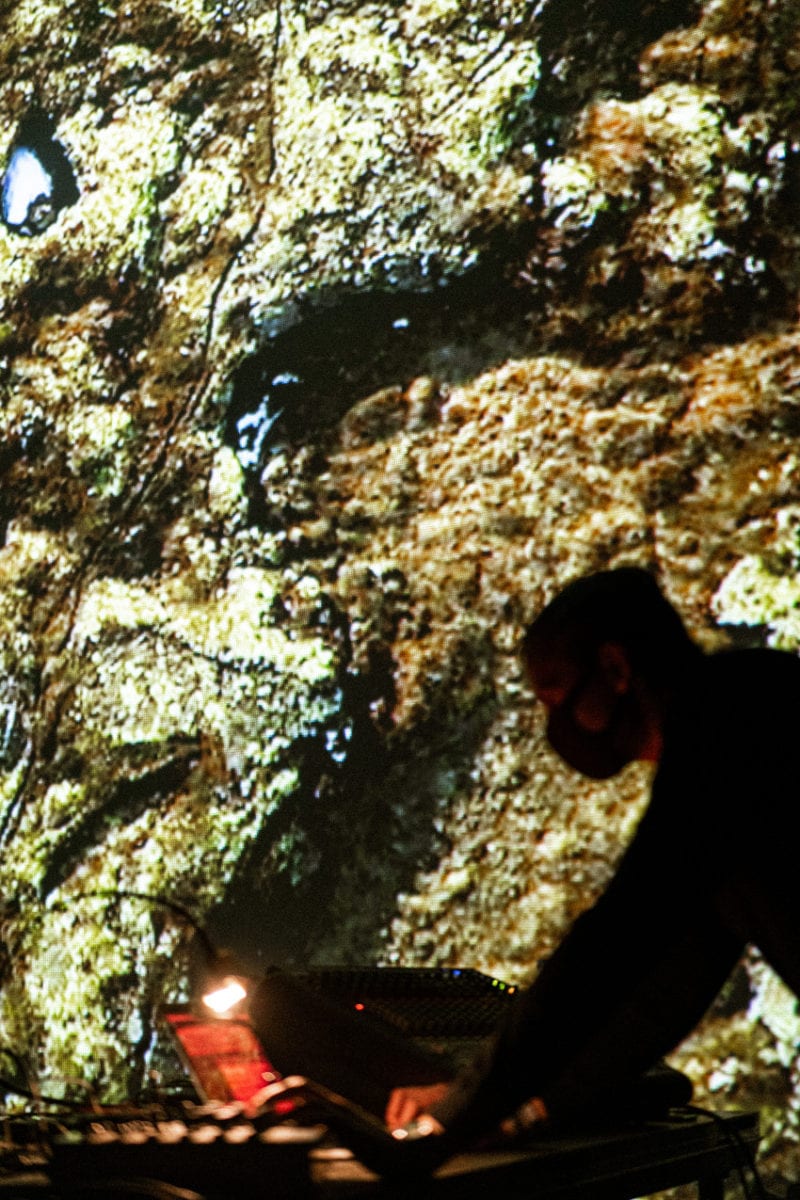

Just as Xynnh demonstrated in the opening event at Ankali, the music made here in Prague seems to be rooted not in genre, or in an attempt to recreate the sounds of other instruments, but more in the practical applications of equipment. Stood, half-obscured by a Eurorack case, Evil Medvěd’s onslaught at the Club stage is exemplary of this fact.

Starting with a trickle, effervescent ambient music popping and clicking around the ears, as their hands fly over the tangle of dials and cables the music shapes and reshapes in ceaselessly creative ways. Tropes of other genres swing by for a visit, but are hardly a focus; breakbeats flutter for an instant in between off-kilter time signatures — a 4/4 beat is a rare find, most often used as a filler before further unwinding into generally unclassifiable territory.

"If Lunchmeat can pull off such an experience under such a restricted landscape, what will they be able to provide next year?"

The visuals are a perfect match. Seemingly curated from humble home footage and simplistic editing procedures to create liquid images, colours and lines leak over one another to create recognisable yet alien scenes, a kind of hyperreality.

There’s a sense of sprinting on the spot: Keya’s footage, framed into three “screens” within the frame, blitzes past in a stop-motion blur. The music matches suit, explosions of modular weaponry hurtling past at hyper speed one minute, before turning on a coin to drop into a glacial pace for brief moments.

As the set progresses, their music becomes less lighthearted, Keya’s imagery shifting in tandem to scenes of state violence the world over. The restless soul possessing the modular gear becomes a malevolent spirit with an explosion of chaotic energy, kicking the floor into anaerobic, staccato dancing. Despite the early set time we leave coated in sweat and breathless, words whisked away by the exhilarating act.

Local act Trauma, no longer able to take their slot on the main stage, are replaced by Berlin act Vū + PRVNTK, who travelled up on the day. Their live set echoes with the taste of Berlin’s nightlife. A rare opportunity to sink into this particular genre of music at Lunchmeat, the Czech crowd lap it up as the rallying mantra of “dance with us” echoes out through the auditorium.

Amsterdam-based Know V.A. have the somewhat intimidating task of preceding the final act, but the pressure doesn’t get to them. In the festival’s last moments, their hybrid live set encompassing myriad musical techniques holds fast, stepping from lyrical beginnings to a hardcore finale.

It’s exactly what we needed to prepare for the final act — hard dance music with soul and weight behind it, flipping through genre and tempo as they guide the crowd to turmoil and frenzy. It’s surprising how little time it takes to find a space for your own, to carve out your own section of the dance floor, the last moments of their set reminding us of liberation we all used to know so well.

At last we arrive at the final set of the night – Sophie. Rumours have been flying through the air as to the set she’ll play, a mystery that deepens as we stand in front of a wall of mist lit neon-green, dense ambient music beating out of the speakers.

It’s hard to tell if time passes or stands still as we wait, but suddenly Sophie steps out of the fog and begins to play. An unsubtle high-gloss blend of just about every club genre under the sun, her maximalist attitude to sound and genre pours out of the PA dripping with sex appeal.

On the dancefloor, eyes roll back in their heads as a kind of feeding frenzy begins. By now we’ve gotten good at dancing in the gaps between others, but during Sophie’s set there’s a deepening of the hive mind that seems to allow for uninhibited movement whichever way you seek to dance.

For all the words in the world, it’s difficult to place exactly what happened between Sophie’s beginning and the end of the festival. Even further, it feels almost wrong to share too much — for an unknown period of time, all those in attendance were synchronised, at one. Telling too much of the tale is almost a betrayal of the intimacy shared.

"Dancing with a mask on isn’t the best fun, but there’s no logic in complaining when it's the key to nightlife"

And with that, all events were finished. A whirlwind of emotions from beginning to end, Lunchmeat impressed immensely — primarily for the dedication of its team, but also the exceptional local artists who showed their colours.

Many ought to look to what was done here for hope and inspiration for events during COVID-19, but understand that there are some bitter pills to swallow for most of us in Europe. The unilateral acceptance of mask-wearing and personal hygiene led to the threat of COVID-19 being significantly lessened within the confines of the festival venues.

The one instance I saw of someone removing their mask inside resulted in their ejection from the festival. As vaguely unpleasant as it is, we must stop regarding public health safeguarding as infringement on our civil liberty. There are more vital fights to be made.

As such, it’s difficult to imagine an event of this kind occurring in London or Berlin any time soon, especially given the context of London’s ‘Plague Raves’. There’s a requirement of unity, of collective and selfless action, which the UK capital at least seems bereft of lately.

Refusing to bow to the encroaching cultural freeze, Lunchmeat worked alongside government demands to produce their event. This might normally be something to turn the nose at, perhaps, but in the current climate this is utterly essential for general societal well-being.

Whilst it seems near-impossible to gather similar support elsewhere in Europe, it might just be a requirement organisers must strive for, if we’re to hope for un-seated events any time soon. Open dialogue is needed between the two entities, which can only exist when there is mutual respect.

This, clearly, needs work from both sides. As cultural consumers we must come up with innovative solutions to the problem, not just lament what used to be. Likewise, authorities which have a say in what events are possible must grant opportunities for trials, and provide the nightlife community with research and open-dialogue platforms for discussion.

It’s so uplifting to be able to talk about the festival that went ahead, instead of filing this alongside the pile of festivals facing bankruptcy. Perhaps it’s a tale of the duality of the fates and human intervention, like a Tolkien-esque narrative pitching the small and defiant against apocalyptic forces, ambition and fortitude against insurmountable challenge.

This extends in no lesser degree to the performances themselves: be it Henke’s monumental undertaking with the CBM 8032 A/V Project, or the likes of Evil Medvěd and Nina Pixel, from the small to the great each act seemed to fight a battle against restriction or limits.

In some cases this is clear, such as with Henke’s use of ‘outdated’ machinery, but in others it was subtle — Nina Pixel’s fight for establishing a queer historical Slovak narrative, or Tadej Droljc’s exceptional live experience summoned from laser beams and sawn industrial steel.

Regardless, all involved with Lunchmeat Festival 2020 mirrored the event’s own incomparable ethic in the face of non-existence. It leaves much to the imagination about what is possible, both in Prague and the wider world, but it also begs a question that will be burning in my mind until October 2021: if Lunchmeat can pull off such an experience under such a restricted landscape, what will they be able to provide next year?

Photography by Eli Eliasek, Jakub Dolezal, Lubosz Branek, Lukas Havlena