"When is dance music not dance music? Is the dance genre defined by its key sonic characteristics or by its actual use in the club context?"

Journalism and discourse has tended to favour the former definition, denoting music as ‘dance’ based on its sonic DNA, propulsive machine rhythms and repetitive melodic hooks, rather than its use on the dancefloor. This makes sense: if any music that was danced to in clubs was considered a part of the ‘dance’ genre then the sonic range would be so vast as to render the term useless. Yet since the dawn of machine-made club music in the late 80s, there have been fringe artists taking dance music and making it un-danceable, fracturing it into broken drum-trips or inverting its tropes to glacial slices of ambience which harbour only the ghosts of house, techno or electro.

So how do we account for dance music which isn’t meant to be danced to, but instead attracts bedroom listeners and commuters? Perhaps some of these listeners are educating themselves in the vast archives of dance music history, or are in fact DJs vetting the latest tunes for potential play. Yet there are far more who will find that dance music livens up their daily activities: listening to propulsive music while working, travelling or walking lends an energy to quotidian life, constituting an escape for many of its listeners.

This musical escape is not unlike the club experience. Dancers go to release the tension built up over a week of drudgery, entering a world where pleasure is priority. They will shuck off their responsibilities, worries and (often aided by stimulants) the construct of their selves. The identity imposed upon them in everyday life is dissolved in the club-crowd consciousness, as each dancer abandons themselves to the single task of losing and finding themselves within the groove.

This, at least, is what the club prophets might say. But this article isn’t about the experience of clubbing, or even the sense of escape that dance music can offer the daily listener. Something else must account for the ubiquity of dance music on the headphones of those resolutely not dancing, as well as the success of myriad sub-genres of dance-not-dance music (to resurrect an apposite yet awkward term).

This article hopes to show that less club-orientated strains of dance music, taking deep house as a case in point, offer the listener not an escape but the opposite: a more nuanced understanding of the world around him/her. When the musical layers are stripped away and the BPM slows, the attentive listener becomes more sensitive to subtle musical changes and slowly evolving melodies. When listened to on the urban commute this increased concentration pervades our perceptive faculties beyond the auditory: the deep house listener becomes more attuned to minute shifts in the fabric of his environment. When heard outside of the club, dance music doesn’t necessarily shut out the listener’s surroundings. It can let the world in.

While the soul-infused deep house of US descent continues to offer brilliant music from artists young and old, it’s the genre’s European sibling which best elucidates this article’s focus. Germanic deep house, championed by labels such as Dial, Kompakt and Smallville (but now adopted by musicians the world over) is one of the most steadfastly melancholy strains of dance music out there.

A hollow 4/4 anchors slow rhythms that are more head-nodding than fist-pumping, while sonic detail is concentrated in the high-end, whether through intricate synth melodies or dusty instrumental samples (often strings and piano). The sounds are unhurried, allowing the listener to appreciate the nuances of texture; tapping patient emotional resonances rather than beckoning the instant rush of euphoria. The aforementioned sonic formula is by no means a hold-all description, however. Often the deep house sound is more stripped, honing in on the subtle interplay of drumkit, bassline and swooning ambient wash. The feature this music has in common, in opposition to big-room dance music, is that it doesn’t tell the listener how to feel. Rather than using the dynamics of tension to create a communion of shared feeling on the dancefloor, deep house trades in subtlety, allowing the listener to explore and indulge his own particular mood, whatever that might be.

There’s something to be said for the road less travelled, not instructing the listener’s emotional response but instead allowing it to be considered and intensified. It also raises an interesting question: does melody move the listener emotionally while percussion moves him/her physically? Like some other genres, notably ambient, the deep house album creates a contemplative space within the listener’s mind encouraging him/her to introspect, to tune in and switch on.

In order to showcase the effect, this article will chart the last five years of deep house music, picking one album from each year. There is no singular feature which unites these releases, but each album shows in a different way how the house album can bear attentive, repeated listens, offering dance music which can have a transformative effect outside of the simple, joyous fact of dancing.

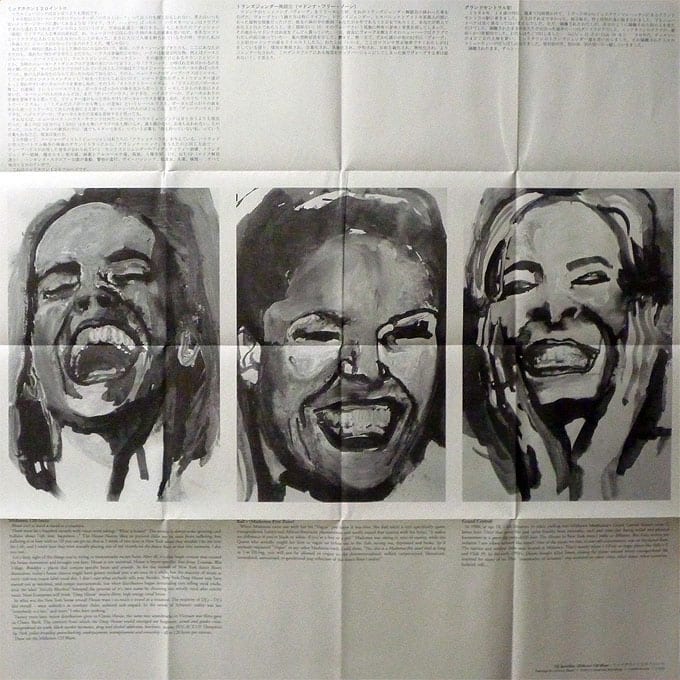

Painting by Laurence Rassel

DJ Sprinkles – Midtown 120 Blues

For an article primarily focused on the German house sound, it may seem odd to start with a release by an American. Yet rather than a typical American house record which might wear its funk and soul heritage on its sleeve, Sprinkles’ muted palette has much in common with European house practitioners; a journey to the centre of the mind, not just the soul.

To anyone interested in house music beyond its dancefloor thrall, Terre Thaemlitz should need little introduction. Gender theorist, dance historian and music academic, Thaemlitz also happens to make some of the finest house music pressed to wax. 2013 was a banner year for Sprinkles, with a remix compilation accompanied by a mix CD, yet we must travel back to 2009 for Sprinkles’ most striking release to date, Midtown 120 Blues on Mule Musiq.

This is so much more than a club album: Thaemlitz uses a suite of lush, melancholic tunes as a springboard for an interrogation of a music which has lost sight of its context. A veteran house DJ who survived the genre’s inception in largely marginalised communities (transgendered, black, latino and queer in Chicago, Detroit and New York), Thaemlitz offers a spoken-word introduction to remind us of the conflict and hypocrisy which birthed our beloved genre and continues to plague it.

“The house nation likes to pretend clubs are an oasis from suffering, but suffering is in here, with us (if you can get in, that is)…house is not universal, house is hyper-specific…what was the New York house sound? House wasn’t so much a sound as a situation… The context from which the deep house sound emerged is forgotten: sexual and gender crises, transgendered sex workers, queer bashing, loneliness, racism, HIV, censorship. All at 120 beats per minute.”

Thaemlitz’ commentary on this and other tracks is ruthlessly incisive, refusing to allow the listener to divorce the music from its troubled and troubling context. Yet Midtown 120 Blues is no dry academic exercise. Instead, the album is a deep house masterclass, a suite of sonic tapestries which combine chunky drum patterns with rich melodic accompaniments, ranging from churning basslines to twinkling synths and melancholic keys.

‘Ball’r (Madonna-Free Zone)’ hypnotises the listener with its steady pulse and subtle keys, before delivering a sharp criticism of the popstar’s crimes of cultural appropriation. Thaemlitz clips the words ‘brothers and’ from the vocal of ‘Sisters, I Don’t Know What The World Is Coming To’ to offer a feminist skew on the conventional house gospel sample bathed in lush, jazzy orchestration. Later the dazzling ‘Grand Central Pt. II’ summons a gaseous ambience, consuming the listener in languid tones and an alarmingly emotionless vocal describing an instance of queer-bashing.

This kind of critique had not been levelled at the genre before, and while it may not have gone platinum, the continued critical coverage of Sprinkles and her ideas in dance media shows that her message did not fall on deaf ears. Thaemlitz’ true stroke of genius in Midtown 120 Blues was to couch her criticism of the house scene not in an essay or article but within an exceptional example of the genre itself. The best way to communicate to house listeners is in the form of house music, and realising this Thaemlitz crafted something challenging, rewarding and beautiful. Each track is a rich miniature, expertly composed with emotional heft: it’s the near-impossible achievement of a house album which makes you think hard and feel hard.

Terre will reissue ‘Midtown 120 Blues’ on CD, with new packaging and poster, sometime this summer through her Comatonse imprint. You can listen to clips of Midtwon 120 Blues via Comatonse

Want more? Check out Thaemlitz’ album ‘Routes Not Roots’ under her K-S.H.E alias.

CONTINUE READING

Part 1. DJ Sprinkles ’120 Midtown Blues’

Part 2. John Roberts ‘Glass Eights’

Part 3. Moomin ‘The Story About You’

Part 4. Recondite ‘On Acid’

Part 5. Kim Brown ‘Somewhere Else It’s Going To Be Good’

Discover more about DJ Sprinkles, Terre Thaemlitz and Mule Musiq on Inverted Audio.

DJ SprinklesTerre ThaemlitzMule Musiq26 January 2009Deep House